Geopolitics and the dogs of war.

The privatisation of foreign affairs.

In this week’s Not in Dispatches, we look at the intersection of geopolitics and the world’s second-oldest profession (alongside all the others): mercenaries.

This is perhaps a natural jump from last week’s edition, in which we examined another constant in foreign affairs: organised crime. Like the Mafia, mercenaries have long been a feature and a bug of most political systems, including the international economy.

History is littered with examples.

There were the soldiers of fortune commanded by King Shulgi of Ur from 2029 to 1982 BCE. There were the privateers like Francis Drake and Walter Raleigh of the 16th century Caribbean.

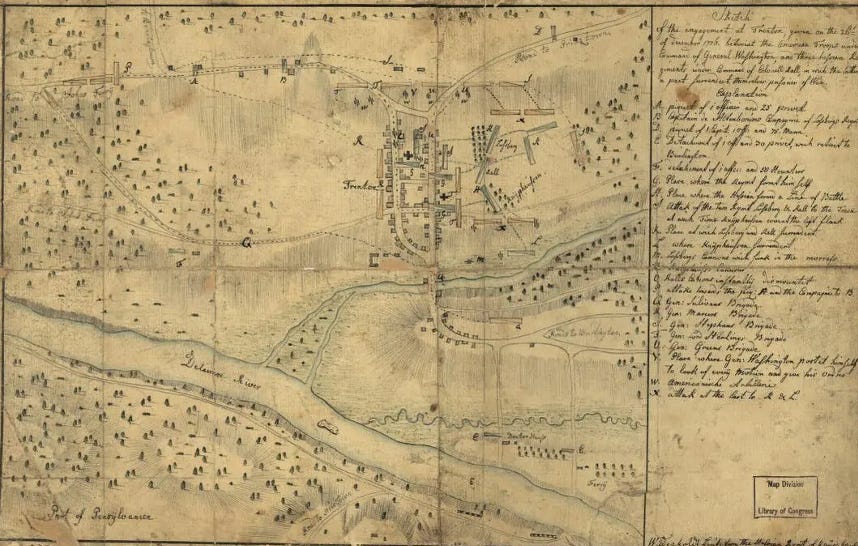

German Hessians were used by the British in the American Revolutionary War (including at the above Battle of Trenton). And more recently we’ve seen the aptly named Blackwater (which now has a more cerebral name, Academi) to which the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan were significantly outsourced.

Throughout this history, mercenaries have had a bad rap. During the Renaissance, Niccolo Machiavelli called them “disunited, ambitious, without discipline, unfaithful; gallant among friends, vile among enemies.”

And today, proving the author of ‘The Prince’ right again, is Yevgeny Prigozhin, perhaps the most famous modern “unfaithful” mercenary. His Wagner Group, which recently terrorised Ukraine, not to mention the outskirts of Moscow, is back to engaging in “vile” conduct across Africa and the Middle East.

Guns for hire.

A mercenary is a civilian paid and armed to do military work in a foreign conflict. Or, to quote Vladimir Putin, a frequent employer of them, they are “instruments for realising national interests without the direct participation of the state.”

Much academic analysis is dedicated to discerning the differences between mercenaries and private military contractors (as well as those between private military companies, private security contractors, and private security companies).

Such fine lines barely matter – every mercenary can work as a PMC and vice versa. Indeed, the Italians, whose competing city-states were constantly at war during the Late Middle Ages, also called their mercenaries “condottieri”. And these “contractors” were organised into “free companies”, the predecessors of today’s PMCs.

Definitions aside, mercenaries, modern and historical, have always had several of the following features:

They are motivated by profits more than politics, although the latter is often decisive.

They are organised as businesses, whether as a band of brothers in the 14th century or in anticipation of an IPO on Wall Street today.

They are expeditionary forces, meaning they work away from home, though they may be stateless.

And they are military outfits that use force, often lethal, to win the battle, rather than police units attempting de-escalation to impose law and order.

Written by former diplomats and industry specialists, Geopolitical Dispatch gives you the global intelligence for business and investing you won’t find anywhere else.

Out in the open.

Notwithstanding their common features, there are different types.

That with which we are all most familiar is the modern overt mercenary. Like Academi, these organisations are ostensibly public and subject to government and media scrutiny, albeit limited. They may, in some cases, operate as an acknowledged arm of the state, be provided for in government budgets, and be held responsible by their shareholders.

The first such mercenary organisation was the armed euphemism, Executive Outcomes. It emerged in South Africa in the late 1980s, around the time of the fall of the Berlin Wall. In a preview of what was to come after the end of the Cold War and the explosion of this mercenary class, EO quelled rebellions, captured oil rigs and diamond mines, and trained militias, all for big money.

It wasn’t until the early 2000s, however, that such mercenaries really took off, with the awarding of contracts by the Pentagon to Erik Prince’s Blackwater and numerous other outfits spawned from elite US military regiments.

And such outfits did much of the work formerly meant for such regiments. Throughout Washington’s wars in the Middle East, there was at least one mercenary for every US soldier. At the height of the Afghanistan War, mercenaries reportedly comprised 70% of US forces.

Governments use such mercenaries because they are more cost-effective than conventional units. They cost nothing during peacetime, as they are engaged by different paymasters elsewhere – they are rented, not owned.

And, during wars, they are much cheaper – the US Congressional Budget Office found that a mercenary unit costs $99 million versus $110 million for an equivalent infantry battalion.

Mercenaries also provide cover for actions of which responsible governments would not be proud – at least, that’s how it is meant to work. During the Iraq War, the killing of 17 civilians by US-engaged mercenaries at Nisour Square in Baghdad prompted an international uproar.

The incident was cited as one of the worst war crimes of the entire conflict and altered the course of Washington’s conventional engagement. Not every denial is plausible.

In the shadows.

Less well understood are covert mercenaries, who only become subject to scrutiny once their cover is blown, and otherwise operate at arms-length from their paymasters.

Given their business model, we don’t know precisely how or where they work or how many billions of dollars are remitted their way. But their methods are likely best epitomised by the already-cited Wagner Group, especially in the form it took before Putin, together with Prigozhin, invaded Ukraine in February 2022. The Kremlin’s rumoured links to it were disavowed, and its ownership structure was under wraps.

Such mercenary outfits are particularly attractive when the client wants to prosecute an unconventional war and to do so silently and on the cheap. The United Arab Emirates is reported to have secretly sent hundreds of special forces mercenaries to fight Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in the ongoing proxy war in Yemen.

The UAE, assumedly through intermediaries, recruited these troops from South America, and their rates were much lower than those ordinarily paid to supposedly more elite Americans and Britons, even though their training and experience, by virtue of their involvement in the long-running drug wars, was top-notch.

Covert mercenaries will also appeal where a conventional force has been unable to solve a problem, whether because of the legal limits on its use of force or because of a lack of domestic capacity or willingness.

For half a decade, the Nigerian government had tried to defeat Boko Haram without much success. After this terrorist organisation abducted 276 girls in 2014, the Nigerian government shifted its strategy and engaged covert mercenaries. They came better equipped and organised than the national military and drove out Boko Haram in a matter of weeks.

Given that their work is often shady, their compensation is often bespoke – covert mercenaries may demand more than cash.

Syria’s Asaad regime often rewards mercenaries who can seize territory from terrorist organisations with oil and mining rights. Indeed, the Wagner Group were reportedly granted concessions in exchange for kicking Islamic State out of central Syria.

With the brevity of a media digest, but the depth of an intelligence assessment, Daily Assessment goes beyond the news to outline the implications.

On the margins.

The distinction between overt and covert mercenaries loses meaning when mercenaries and private security contractors are employed not by states but by non-state actors. And, in our post-end of Cold War era, the number of non-state actors willing and able to hire mercenaries is increasing, perhaps exponentially.

Multinational corporations, especially in the resources sector, are the fastest-growing client set for private security.

Forbes reported in 2012 that American mining company Freeport-McMoRan engaged Triple Canopy (which has since merged with Academi). The American organisation was tasked with protecting Freeport’s copper mine in Papua, Indonesia, from an insurgency.

Chinese corporations, especially those involved in Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, are also increasingly mercenary dependant.

The China National Petroleum Corporation contracted with DeWe Security to safeguard assets threatened during South Sudan’s civil war. China also reportedly uses Wagner to protect a range of BRI projects.

Non-government organisations are also joining the fray, or at least private contractors want them to – Triple Canopy and the British security company, Aegis Defence Services, have reportedly advertised their services to NGOs as well as NGO trade associations. Less to win wars and more to protect volunteers in dangerous parts.

Of graver concern is the emerging trend of mercenaries offering their services to, as opposed to in service against, terrorist organisations.

Malhama Tactical, which is based in Uzbekistan, reportedly offers military trainers, arms dealers, and elite warriors to Islamic extremists, including the Nusra Front, an al Qaeda-affiliated group, and the Turkistan Islamic Party, a Uighur extremist group based in China.

And, of greatest potential for Hollywood adaptation is the growing prospect of high-net-worth individuals engaging mercenaries to prosecute their own idiosyncratic agendas. A Financial Times report in 2008 recounted actress Mia Farrow’s request for Blackwater to intervene in Sudan’s Darfur region.

Whether overt, covert, or operating independently and even in despite of government, mercenaries have been on the rise over the last 30-plus years. Some private units are now better equipped and more effective than many conventional militaries. And all are enjoying a growing client pool.

For as long as we can remember, states had a monopoly on force, at least officially. Now, it’s an increasingly competitive market, and there are untold consequences for our international order and businesses operating in the increasing number of states where mercenaries play a role.

Despite these challenges, we hope you are enjoying these Not in Dispatches and our Daily Assessments as much as we are. We would be most grateful if you could refer Geopolitical Dispatch to a friend or colleague.

Best,

Michael Feller, Cameron Grant, and Damien Bruckard, co-founders

Emailed each weekday at 5am Eastern (9am GMT), Daily Assessment gives you the strategic framing and situational awareness to stay ahead in a changing world.