Great southern land

The geopolitics of Australia.

In this week’s Not in Dispatches, we take a look at the world’s oldest, driest, smallest, flattest, most infertile and climatically unpredictable continent – and our home country, Australia. It’s a longer article than usual, but there are almost 3 million square miles to cover.

History’s page

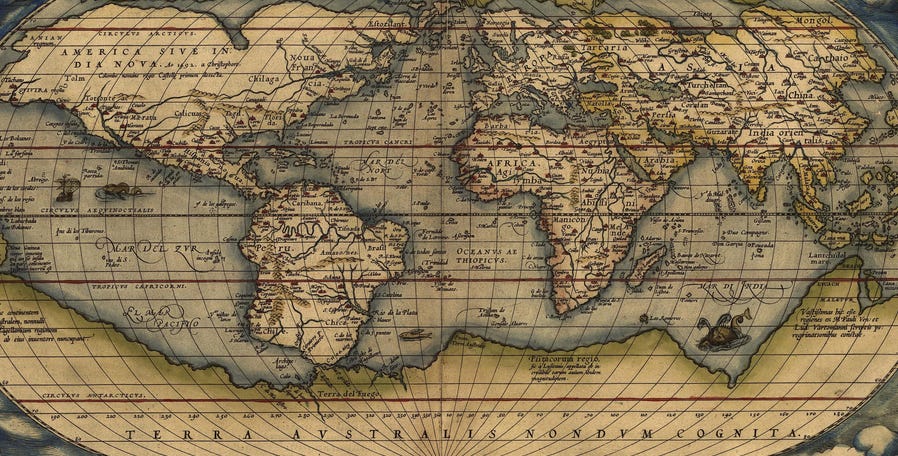

The name Australia derives from the Latin australis, meaning southern, and dates to second-century legends of an “unknown southern land” – terra australis incognita.

The name first appeared on maps, like the one above, based on speculation that there must be a southern landmass to balance the northern hemisphere. But it wasn’t until the 17th century that European explorers finally found this continent. And, since they were Dutch, it naturally became known as New Holland.

Australia, of course, has a much longer history. Indeed, its first inhabitants – the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders – have been there for around 60,000 years, making them the oldest surviving culture in the world. At the time of European settlement, the indigenous population was large (estimates range from 300,000 to one million), with over 200 separate nations speaking over 250 languages.

Like many New World conquests, however, European settlement decimated the original inhabitants. Through a combination of guns (deliberate killings and frontier wars), germs (smallpox, influenza, measles, and tuberculosis) and steel (industrial technology and the clearing of land), colonisation had a disastrous effect on indigenous Australians. Not only were they dispossessed, but their population dropped by over 80%. Only recently has it surpassed its pre-1788 number.

Modern Australia’s original sin – only recently admitted by society – was the destruction of this indigenous world. And modern Australia’s history has been haunted by this sin, as well as by geopolitics.

Wild colonials

Australia’s modern history could have looked very different.

In the 18th century, the French, Dutch, Spanish and British were all on the lookout for colonies. Dutch explorers first mapped the Australian coast. A Frenchman was the first to claim sovereignty. But ultimately it was the British that colonised Australia. And Britain’s multiple motivations for doing so still shape Australia’s outlook on the world.

The British settled Australia for a mix of geostrategic and political reasons. At the time, Britain’s jails were overflowing. England had a wicked combination of high crime rates, a low bar for what constituted an offense (e.g., starving children stealing food), and no police force. For decades before arriving in Australia, London dealt with this problem by transporting prisoners to North America, a policy deemed more humane than execution. But after the American Revolution, they ran out of room.

Australia, which the British considered uninhabited – disingenuously invoking the legal doctrine of terra nulius (‘nobody’s land’) – made for a perfect solution.

Not only would Britain’s pesky prisoners, especially the rebellious Irish, be far away, but Australia’s geography made it a strategic location. Close to the Spice Islands and India, the penal colony of Sydney Cove was a useful tool in keeping the French and Dutch from shutting Britain out of Asian trade. Australia could be established as a fortress, using convict labour, and would make a good base for British ships “should it prove necessary to send any into the South Seas” (as one official suggested).

And the good weather, officials thought, would be better for the convicts’ health and redemption.

Australia’s modern history thus began as a Western outpost in Asia.

Terror Australis

Even if some thought Australia’s better weather would be beneficial – as almost all tourists do today – life in the colonies was tough.

While the indigenous population suffered most, the early Europeans also struggled. Many convicts were political prisoners, primarily of Irish descent. Transported against their will, they, their prison guards, and the free settlers alike faced a harsh environment. Unlike America, founded as a religious experiment where Europeans (for the most part) arrived by choice, in Australia they arrived in chains.

And this history has shaped Australia’s national character and its outlook on the world.

Far from home, convicts and officials felt abandoned and insecure. In the contemptuous cohesion of the convicts – of whom 80% were male – lay the roots of Australian egalitarianism, resourcefulness, irreverence, ‘mateship’ and machismo. Perhaps more than anything else, this brutal system made Australians (in the words of historian Robert Hughes) “cynical about authority, or else it made them conformists”.

Today, like their colonial ancestors – both prisoners and guards – many Australians remain cynical conformists, with a hybrid respect for order and disdain for pretension.

Australians, unlike the British, call their prime ministers by their first name or irreverent nicknames – just ask Hawkey, Little Johnny, ScoMo or Albo. And unlike the British, they take these leaders with a reverence that would be considered strange in the “old country”. Though Australia’s parliament is built into the ground, allowing (in theory) visitors to walk over its members, the politicians are among the most highly remunerated in the world, with large staffs, chauffeured cars, and almost zero expectation of constituent surgeries.

Though they call their prime minister Albo or just ‘mate’, Australians generally fear authority. And for all its contemporary multicultural character, Australians like to pretend they’re all identical (it helps that all males have the first name ‘Mate’). And for any foreign investor perplexed at the miles of red tape, don’t blame the bureaucrats. When Australian voters see a problem, the answer is always, invariably, more government regulation.

Golden soil

Australia changed from a prison to a quarry when gold was discovered in Clunes, regional Victoria, in 1851.

Australia’s population exploded. It became multicultural and spectacularly wealthy. By the end of the 19th century, it had the highest standard of living in the world. And over the next five decades, a national identity developed, the six colonies united, and Australians sought independence – which they got, through not revolution but by an act of parliament.

Once independent, at least formally, Australia became a leader in progressive democracy. It was the first country to grant women the right to vote and the right to be elected. Australians invented the secret ballot, the eight-hour working day, and wage arbitration. And its convict origins created not only an irreverent national character but the conditions for a strong trade union movement, which lasts to this day (albeit for most in the form of giant union-owned pension funds).

Australia has an abundance of coal, iron ore, aluminium, zinc, gold, copper, gas, rare earth elements and uranium. In the 1850s, it was gold that delivered the wealth. In more recent years, it’s been iron ore, coal and gas for China, India, Japan and Korea. Until Covid-19, Australia had spent three decades without a recession – a record for a developed country. With the living standards of Europe, but proximity to Asia, it was indeed the lucky country.

Wealth for toil

But Australia’s fortunes have not been evenly spread. Its rugged geography and harsh climate – impoverished soils, lack of water and searing heat – have restricted most settlement to the coastal belt. Most Australians today live in just one of five large port cities – Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth – whose economies revolve around the lifestyles of the inhabitants and financing Australia’s mines and farms deep in the interior.

Australia has, in essence, always been a quarry and a farm with nice beaches and good cafes (that serve flat whites, Australia’s latest export). As a consequence, it has always struggled to diversify. Australia ranks 93rd in the world for economic complexity, its closest peers being Uganda and Pakistan. The manufacturing sector has all but died, with a small domestic market and cheaper labour in Asia. And the laws of comparative advantage have made pivoting to other industries expensive and futile, government efforts and rhetoric notwithstanding.

Yet thanks to some luck, and the legacy of British legal institutions, Australia has managed to avoid the ‘resource curse’.

The result is that Australia today is extraordinarily wealthy. Credit Suisse in 2022 ranked Australians the richest in the world, with the median adult worth more than $225,000. The average full-time salary is over $65,000, with most Australians benefitting from a generous pension system. Various ‘liveability’ indexes regularly place its cities in the top ten globally. And on most metrics, Australians have it bloody good: stable politics, low crime, high incomes, and relatively low (albeit increasing) inequality.

Australia, in some respects, resembles a resort: great weather, a full buffet (for most), and very little to worry about, other than to remember the sunscreen.

This “comfortable and relaxed” existence – the mantra of conservative prime minister John Howard (1996- 2007) – has had profound social, political and foreign policy implications, especially combined with the country’s physical isolation from the world.

Geopolitical Strategy is the advisory firm behind Geopolitical Dispatch. Our partners are former diplomats with vast experience in international affairs, risk management, and public affairs. We help businesses and investors to understand geopolitical developments and their impacts with clarity and concision.

Aussie rules

Australians inherited the British knack for small talk. Conversations kick off with questions about what school you went to, what football team you support, what suburb you live in, how is the weather, and what about interest rates. But, unlike the imperial centre, Australians also developed an internalised inferiority complex that still manifests in what is locally known as “tall poppy syndrome” – intense scrutiny and criticism of people their peers believe have become too successful or who brag about their success.

The flip side is that many of the elite have, in turn, adopted the “cultural cringe” of their 19th-century forebears, the “bunyip aristocrats” who lived in denial of their antipodean geography and convict compatriots. Just as their forebears retreated to English-style clubs, today’s inner-city elites insulate themselves in flat whites, chardonnay, and expensive fusion cooking. And just as their forebears aped the styles and snobberies of Victorian London, today’s adopt the politics of San Francisco and Berlin, with little thought as to how this might resonate with a population who love nothing better than to lampoon such conceits.

Australia’s complexion today looks much different from the 19th century, following mass immigration. Successive waves from southern Europe, India, China and the Middle East have made Australia one of the most multicultural countries in the world. Today, almost a third of the population was born overseas (compared to around 15% for the US, UK and France). And Australia has had, by and large, a successful migrant experience, with a relatively harmonious, integrated and tolerant multicultural society. (The exception being indigenous Australians who still suffer extensive disadvantages.)

“Comfortable and relaxed” Australia, plus its anti-intellectualism, means its politics is less about big ideas than a form of sport, the national religion.

People are passionate about politics, but at a superficial level. Forced to vote since 1924, Australians figure they might as well adopt a team. But they do not join parties in large numbers. Most civic protests are just students who have found their tribe. And compulsory voting means the major parties must compete for the median voter, appealing to a middle class of high-income, risk-averse and (increasingly) debt-ridden urban property owners.

One result is that Australia’s domestic politics is boring. Few want to rock the boat. Australians may mock their leaders, but they listen to them and turn to the government to solve their problems. Its civil service is professional and largely free of corruption. It’s derided in the irreverent culture, but for the most part delivers high-quality services. And its politicians have largely eschewed extremes.

Voter nonchalance has been the major reason behind the failed attempt to become a republic (1999), the perennially stalled movements to change the flag, and most recently, the unsuccessful referendum to create an indigenous advisory council to parliament (2023). All failed less out of Anglophilia or xenophobia, and more out of an “if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it” attitude.

Under this attitude lies an aversion to risk. Firms in Australia are, in many ways, insulated from global competition and challenges. Most Australians don’t valorise entrepreneurs. Businesses tend not to innovate, and investors prefer sure bets. Capital (except for real estate, Australia’s second religion) is tight and big business dominates the economy. There is a duopoly for groceries and airlines. Four major banks dominate the market. And despite 26 million consumers, there are just a handful of telcos, insurance companies and logistics providers. One company owns the toll roads. Nothing is cheap.

The combination of Victorian-era sensibilities, a convict heritage and risk-aversion has led to a phenomenon that Australians simply love rules. Australia may think it has a Wild West spirit or an obsession with freedom, but unlike the Americans they sometimes think they are, Australians relish regulations, applaud restrictions for the greater good, and readily dob-in rule-breakers and moralise foreigners like the loyal, law-abiding and pious colonists of old.

Australia was the first country in the world to introduce mandatory seatbelts. After a mass-shooting in the 1990s, one million guns were quickly banned, collected, and destroyed, almost without protest. And when Covid struck, Australians embraced lockdowns, pulling up the drawbridge over the world’s biggest moat, closing the borders between states, and sanctimoniously self-enforcing compulsory mask-wearing. It was not unusual to see people driving alone in the cars with the windows up and wearing masks.

As for many countries, the pandemic allowed Australians to show their true colours. Just as the Chinese obediently followed totalitarian measures, the French saw rules to be broken, the Russians fatalistically accepted mass deaths, and the Americans saw conspiracy, Australians went hard at keeping out foreigners, demonising Asia, and assuming the guv’nor knew best.

Tyranny of distance

Australia’s essential national experiences and character have naturally shaped its view of the world. But so too has its geography.

Despite changing demographics, Australia has, and likely always will be, a sparsely populated Western outpost in the Pacific, far from its markets and the places from which most of its population originally comes.

Australia’s strategic dilemma has always been how to defend itself. Its preoccupation has always been seeking protection from empire – first, Mother England and then, America. And its anxiety has always been a fear not of foreign entanglement, like America, but simply of being forgotten about.

Australia is, by any measure, a secure country. It is a continent unto itself, with no belligerent neighbours and a ‘strategic depth’ most would dream of. It is girt by sea. And it has been far from the most devastating events of the past 200 years. While Australia fought in both the first and second world wars, this was always on foreign soil (the closest shave being the bombing of Darwin and three Japanese submarines in Sydney Harbour).

And yet Australia has an insecure mindset – which has led its foreign policy to always rest on three ‘FOMO’ pillars – having a “great and powerful friend” for protection, supporting the “rules-based international order” (known elsewhere as the American-led order), and, in the best tradition of Viscount Castlereagh of Napoleonic Europe, ensuring that Southeast Asia is not dominated by any single great power.

Team America

Most important in understanding Australian foreign policy is its adherence to the American alliance, which also has its roots in culture.

Australia and America need each other. Deeply insecure, Australia has never felt comfortable without the protection of empire. Indeed, modern Australia has only ever existed during times in history where Anglophone countries ruled the world. Australia’s sense of being out of place in Asia has always made its people and policy elite anxious about potential invasion from the north. And its cultural, linguistic, and political affinities with Britain and America have made it relatively seamless to pursue alliance at whatever cost.

Australia followed Britain into both world wars and America into Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq. This wasn’t because Australia had vital interests – though some were confected and genuinely believed – but because it was making a down-payment on its geopolitical insurance. The primacy of American protection for Australia’s security means Australia will almost certainly enter any war America wants it to join – even over matters peripheral or against its interests.

America also needs Australia, which is the biggest unsinkable aircraft carrier in the world. Australia has myriad ghost air bases in the desert. It hosts a major American signals base at Pine Gap. The second-in-charge of the Indo-Pacific Command is an Australian. The Navy has a USS Canberra. And Australia will not only toe the American line, but will be its biggest cheerleader, including on matters where America cannot or will not speak out. Whereas once, Australians were ‘more British than the British’, today they can be ‘more American than the Americans’.

America’s waning influence in the world, as it transitions from a US-led order to some form of multipolarity, poses a profound foreign policy challenge for Australia. The lucky country will have to get used to, for the first time, a world where its greatest ally is not the hegemon. But Australia can take solace in the fact that America will only likely give up on Australia when it gives up on Alaska, Hawaii, and Guam, its other three unsinkable Pacific aircraft carriers.

Australia’s signing up to the AUKUS military pact was unsurprising. It was not just a reflexive cuddling up to mum and dad, but was consistent with Australia’s history, character, and anxieties.

Emailed each weekday at 5am Eastern (9am GMT), Geopolitical Dispatch goes beyond the news to outline the implications. With the brevity of a media digest, but the depth of an intelligence assessment, Geopolitical Dispatch gives you the strategic framing and situational awareness to stay ahead in a changing world.

Fatal shore

Australia’s strategic dilemma can also be seen as being caught between history and geography.

Australia’s fear of Asia has been prevalent since the earliest days of European settlement. In the 1850s, tens of thousands of Chinese flocked to Australia chasing gold but also finding the ‘mateship’ amongst the ‘diggers’ did not extend to them. Xenophobia led the colonies to pass many anti-Chinese immigration laws, including policies only fully dismantled in 1973, in part due to international pressure.

Antagonism towards China has been present in Australia since, but flared up particularly strongly in the move towards Federation, at the height of the Cold War, and, most recently, in response to Xi Jinping’s foreign policies and America’s regional equivocation.

Australia’s own foreign policy has fluctuated from seeking security in, and seeking security from, Asia. High points for engagement have been Australia establishing relations with China (1972, seven years before the US), proposing APEC (1989), joining the East Asia Summit (2005), and concluding free trade deals since 2003 that culminated in the regional CPTPP and RCEP agreements.

But Australia’s approach to Asia has always been relatively transactional, hemmed in by the greater interest in preserving the American alliance, and constrained by perceptions in the region that Australia, however it presents itself, is not really ‘Asian’.

In recent years, Australia’s engagement in Asia has been a mixed bag. Relations with China deteriorated sharply after 2016, and by 2020 Chinese sanctions had been applied to many Australian exports. Japan is Australia’s closest partner in the region, similarly caught between an American ally and the Chinese market, but Tokyo’s pacifist constitution makes it a mostly commercial partner. Australia has a strategic partnership with India, but it remains mostly one of cricket and migration. And Canberra’s so-called Pacific ‘step-up’, involving a concerted effort to be less condescending and more attentive to island nations, has occupied significant attention but with few results.

Order!

Unsurprisingly for a middle power, a third constant in Australian foreign policy is its support for the ‘rules-based order’, open trade, and multilateralism.

Australia, like many nations, has done well from the American-led international order. It has prospered and had no real challenge to its security. The steady march of globalisation with increasingly open trade in goods, services, and capital, combined with the rise of Asia and its insatiable appetite for rocks, has only been beneficial. And as an exporting nation, the rules underpinning this world order – including the WTO disputes system and open shipping lanes – have allowed Australia to become among the richest countries in the world.

The progressive weakening of this system, in large part caused by a decline in American leadership and a worldwide rise in protectionism and nationalism, is perhaps Australia’s most significant challenge.

As the world transitions to a multipolar order, Australia will likely remain the 51st American state. Since the US will have less influence in Asia, Australia will have less influence in Asia. And because the US will have fewer options, Australia will have fewer options too.

An emerging multipolar order will likely see Australia and India move closer. A reasonably familiar country – English-speaking and cricket-mad with a vaguely Westminster style of government – India is now the fastest-growing source of Australians.

The first country with which modern Australia traded (the British provisioned Sydney from Calcutta), and the place from where archaeologists believe many of the first Australians originally walked (and where Australia’s famous dingo originated), the future, as well as the past, could be in India.

For the rest, the future of terra australis will remain incognita.

Beautifully written