Irregular: Inaugurating the Geopolitical New Year

How to Plan for Trump 2.0

Hello,

In today’s Irregular column, I want to wish you a prosperous Geopolitical New Year.

While the calendar year begins on 1 January, Orthodox New Year on 7 January and Chinese New Year on 29 January, the Geopolitical New Year kicks off on 20 January with the inauguration of the second Trump Administration. In fact, in many ways, it’s the beginning of a four year geopolitical cycle that promises to be very different to the past four years.

You’re Hired

Donald Trump’s re-election poses many uncertainties for international relations.

Trump deliberately cultivates unpredictability, says many outlandish things, and – as a man who lives to bargain – has a particular penchant for making ambit claims, creating leverage and taunting interlocutors before settling to get the best deal. While it is often hard to distinguish the rhetoric of politicians from their real intentions, it is doubly hard when trying to predict the actions of a showman who loves the spotlight, is prone to exaggeration, and is often loose with the truth.

That makes forecasting Trump’s foreign policy – and how the rest of the world will respond – challenging. While we are largely in a “wait and see” mode, one thing we can be sure of is that the next six months will be messy and full of turbulence, uncertainty, novelty, and ambiguity.

There are some things, however, that we can say with a high degree of confidence.

Trump, unlike Biden and many of his predecessors, is isolationist and protectionist, hostile to illegal immigration, and sympathetic to authoritarian strongmen. He sees little value in international organisations and international law. He is bent on renegotiating relationships to make allies pay more for US protection. And he is a man who likes to get his way.

While much of what Trump has said on the campaign trail and during the transition phase could just be bluster (e.g., the Great State of Canada), overall, we advise taking him at his word.

This means taking seriously the possibility of US withdrawal from NATO, a weakening of the Western alliance system, greater confrontation with China (at least in the short-term), and a tariff war with much of the world. But it also means taking seriously Trump’s commitment to avoid entangling the United States in more “forever wars” and, above all, his oft-professed overarching foreign policy goal of avoiding a third world war.

Interesting Times

The transition to the second Trump Administration is happening at the most geopolitically perilous time since the end of the Cold War.

America’s global leadership is increasingly contested as it confronts domestic challenges, turns inward politically and economically, and contends with the rise of other powers, particularly China. The “no-limits partnership” between China and Russia, despite being unnatural allies with historic enmity, signals a concerted effort to challenge US dominance and rewire the global system. Emerging powers, particularly India, are adopting a more global, independent and assertive role, reshaping the global system. And multilateral institutions at the core of the liberal “rules-based order”, such as the UN and WTO, have been struggling to adapt to growing divisions between member states – and it’s by no means only Donald Trump who views them with disappointment and derision.

Donald Trump is taking office for a second time in a world that is more challenging than eight years ago, not only for the United States but for businesses operating across borders.

The immensely destructive wars in Ukraine and the Middle East show few signs of abating. The Eurasian powers – China, Russia and Iran – have become even closer and more united, with the BRICS continuing to expand, even as each of those “great powers” may have individually lost some influence, with China’s economy slowing, Russia bogged down in Ukraine, and Iran’s proxy network decimated. And the host of other geopolitical flashpoints, especially in East Asia – from Taiwan to the Korean Peninsula to the South China Sea – have hardly gone away.

Taking a step back, as we’ve written about quite often, it appears clearer and clearer by the day that an era is ending – the era of the so-called “liberal rules-based order”.

All dimensions of that important-yet-hackneyed phrase are now in question. And perhaps the most important thing for organisations to consider, beyond more immediate and tactical concerns around tariffs and policy shifts, is the strategic issue of whether the existing order will survive, how it might change, and what it means for the business environment.

Four logical questions present themselves.

Four Questions, Four Years

The first question is whether the international order will remain liberal. Liberal, in this context, often means generally supportive of human rights, freer trade, democracy and multilateral cooperation. Trump is not so keen on free trade, is willing to deal with autocrats and, unlike more ideological predecessors who have divided the world into democracies and autocracies, does not believe in an American manifest destiny to remake the world in its own image. Without a United States insisting on the international order being liberal, might we suddenly see all the great powers – the US and China and Russia – aligned on a thinner vision for world order, based more on common interests than common values?

A second question is whether the international order remains “rules-based”. Perhaps this notion has always been somewhat aspirational or insincere. But Trump certainly does not like to be bound by rules, and often shows contempt for laws, courts and institutions – both domestically and internationally. For Trump, while international rules may not be made to be broken, treaties and bilateral relationships more broadly are certainly up for renegotiation. Just as Trump withdrew from the Trans Pacific Partnership on his last first day in office, immediately began to renegotiate NAFTA, and attacked the Paris climate change and Iran deals, might we see the us withdraw from even more international agreements amid a broader erosion of what’s left of any international rule of law?

A third question is whether the international system will remain orderly. Trump revels in uncertainty, approaches “peace through strength”, and strategically and by disposition both picks fights and, when he does, pulls few punches. It’s very likely that Trump will open with a show of American strength – especially towards China, but also countries like Mexico and Canada with whom the US has a large trade imbalance – for the purpose of creating leverage and renegotiating bilateral relationships more in America’s favour. And with aspirations for grand bargains — over Russia/Ukraine, the Middle East and, most of all, China — this may be a moment where the old order is redefined or becomes decidedly less orderly. Above all, we’re looking at an American foreign policy transacted more bilaterally, with more hostility and more turbulence, raising a very important question of whether this will lead to greater or less stability.

Finally, while it does not appear in the phrase “liberal rules-based order”, there’s the implicit part of the phrase that often goes unspoken — “US-led”. American leadership too is in question. Trump has often espoused classic isolationist views, railing against “forever wars”, voicing suspicion of alliances, and promising not to get involved in conflicts unless there are vital American interests at stake. But several key Trump advisors are much more bullish on support for Ukraine and Israel, hawkish on China, and comfortable deploying the American military in faraway lands. While Trump will want America to remain top dog, there remains a question about how it will lead, who it will lead, and on what issues. And there’s an even bigger question of whether it will support the international system it created, or actively work to undermine it.

Day One

These questions matter.

Businesses and investors have much at stake. A more “illiberal” order could lead to more protectionist measures, not only from the US but its partners (with industry winners and losers), making cross-border commerce more complicated. A less “rules-based” system could change the nature and force of international laws. A less “orderly” world could ratchet up tensions and risks of conflict, while a more “orderly” world with accommodations between the great powers could re-open hitherto closed and sanctioned markets. And the retreat or return of American primacy will be a major factor in whether international rules governing business will be written largely by “the West” or “the Rest”.

Inauguration Day will provide slightly more clarity — at least about Trump’s intentions and early priorities. But that will not be the end of it. The nature of foreign affairs mean that much is done on the fly. It’s reactive. And insofar as Trump may have a vision for America and its place in the world, he is above all opportunistic, and will spend much of the next four years not only setting the agenda but reacting to an unpredictable world.

And so there are even more uncertainties organisations will have to grapple with – not out of some academic or theoretical interest, but because they will directly impact the international business environment. Matters like:

How will China react to a second Trump Administration and will the relationship become more confrontational or cooperative?

Will the Eurasian powers — China, Russia and Iran especially — that have in recent years hardened their opposition to the US become closer allies or split apart?

Will Trump’s hardball negotiations with allies ultimately bring them closer (e.g. through greater NATO spending) or drive them apart?

And can Trump, even if he wants to, negotiate a peace deal over Ukraine when there are few incentives for Zelensky to cave or Putin to stop?

These are just some of the questions on our minds and what our clients are asking us. Definitive answers, however, are hard to come by.

Scenario Planning

That’s why we use scenario planning as a method for thinking through what the world could look like and what the business implications could be. This involves taking uncertainties – like the ones above – assessing their likelihood and ranking their impacts, generating plausible and mutually exclusive scenarios, and thinking through what each would mean for an organisation’s specific interests.

Scenario planning doesn’t tell you what will happen. Rather, it provides a framework for seeing the various ways events could develop and a structure for analysing their impacts — thereby allowing for a productive discussion on how an organisation can strategically position itself in an inherently uncertain world.

When we do this with clients we don’t just produce scenarios about what the world looks like. We are much more precise. We work with clients to define clear focal questions to make sure we’re asking questions of direct relevance that will identify precise risk and opportunities bespoke to that organisation. And, even more importantly, once we have helped identify those risks and opportunities, we work with executives to stress test their current strategy, identify “all weather” moves that will hold up in multiple geopolitical scenarios, and design monitoring systems to ensure organisations can adapt to change.

After all, if there’s one certainty arising out of the Geopolitical New Year, it’s that there will be more uncertainty. And that’s precisely what these methods, used by leading companies and intelligence agencies, are designed to help organisations deal with.

If you would like to learn more about how can help you develop a robust geopolitical strategy please don’t hesitate to get in touch.

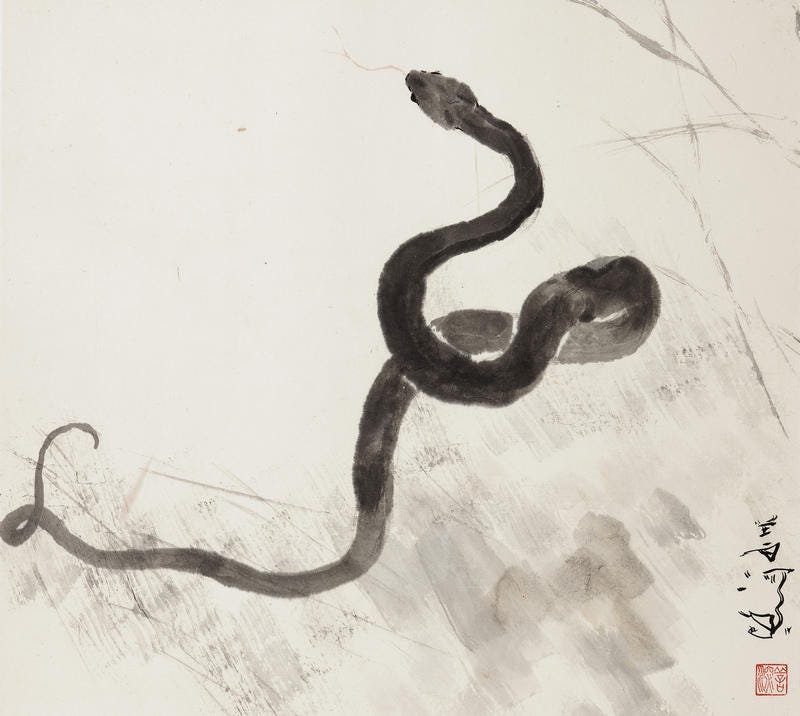

In any case, wishing you all the best for the Geopolitical New Year – perhaps ominously also the Year of the Snake.

Warm regards,

Damien Bruckard

CEO, Geopolitical Strategy