The geopolitics of food.

Guns and butter.

In this week’s edition of Not in Dispatches, we examine the geopolitics of food. Everyone likes food and we know you like geopolitics. So hopefully this will be a good pairing.

First, however, a small request before the main course.

If you are enjoying Geopolitical Dispatch, please help us by forwarding this article to a friend or colleague, or clicking share below. In the few weeks since our launch, we are now read by hundreds of leading business and political decision-makers in 64 countries. But to make our efforts sustainable, we need to increase our readership.

We believe Geopolitical Dispatch offers a unique service of summarising the day’s key strategic developments and delivering actionable analysis in the shortest space possible. We don’t think anyone else produces so much information in so few words.

Let them eat cake

Sitting at the base of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, food is fundamental for human survival and therefore a primary concern of governments the world over – a resource to be protected and, sometimes, weaponised.

The Black Sea grain deal, which one of our co-authors was closely involved in, makes for a good illustration.

Russia’s early war strategy included shutting off Ukrainian trade routes to starve it of the resources needed to resist the invasion; the West’s response included sanctioning Russian fertiliser. Both had major implications for countries all over the world, especially in Africa, which were highly dependent on both Ukrainian wheat and Russian fertiliser.

With a humanitarian crisis looming, Turkey and the UN stepped in to broker a deal for the resumption of trade in exchange for a relaxation of sanctions. Now, the deal is at risk of collapse. Russia’s incentives to keep it going are diminishing as it brings new fertiliser pipelines online and shifts its trade to non-Western markets. Meanwhile, previously vulnerable countries have become less reliant on Ukrainian exports. But Moscow has also become more dependent on China and Turkey, which both want the deal extended. Take any confident predictions with a grain of salt

Written by former diplomats and industry specialists, Geopolitical Dispatch gives you the global intelligence for business and investing you won’t find anywhere else.

War and peace

Sieges and blockades have long been tools of war.

The Nazis surrounded Leningrad for 872 days, killing over a million. In the 1990s, the Bosnian Serb Army besieged Sarajevo for nearly four years. The Assads and Hezbollah encircled Madaya in Syria. And the Saudi-led air and naval blockade of Yemen exacerbated a humanitarian catastrophe putting millions at risk of starvation. War, as historian Will Durant put it, “is a nation’s way of eating.”

But the weaponisation of food occurs in peacetime too.

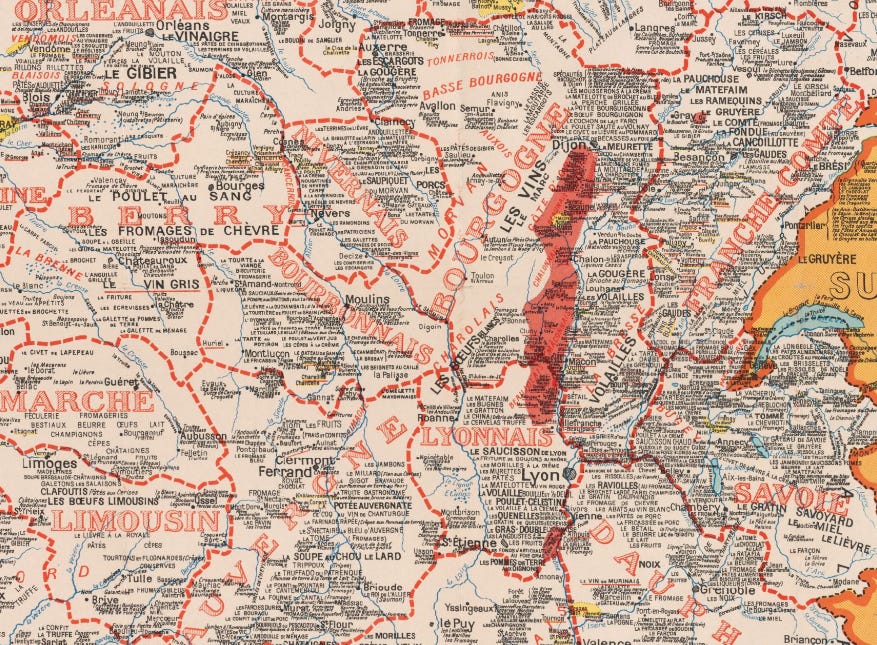

Governments extensively protect their agricultural producers through trade policy. Tariffs are used to make imports more expensive, providing subsidies to offset the cost of domestic production. Agriculture ministries fiercely insist on intellectual property protections for flagship goods. (A co-author is presently writing from Cognac on Bastille Day, though sadly without either a glass of the brandy or of Champagne, both protected by “geographical indications” under international trade law).

Not only do countries protect agriculture for their own food security, they do so to appease powerful political interests.

French farmers’ anxieties about competition from Brazilian ranchers prevented the EU-Mercosur agreement from being finalised. Trump’s trade war with China was driven as much by protecting soybean farmers as containing a rising geopolitical rival. Last year, India banned rice exports to lower consumer prices. This echoed the fears that gripped Mexico in 2011 when financial speculation and biofuels subsidies drove up corn prices and led to the “tortilla crisis”.

Just as food can be a victim of geopolitics, geopolitics can be a victim of food politics.

What’s that got to do with the price of fish?

Rising food prices, especially of staples, can cause serious political instability.

The Arab Spring may not have happened without a doubling of food prices from 2006 to 2008 and a secondary spike in 2010. Today, the UN warns that 22 countries (mostly in Africa and the Middle East) are facing acute food insecurity driven by conflict, economics and climate change.

And the combination of high food and energy prices, rising interest rates, and increasingly unmanageable public debt burdens mean that many societies could be sitting on a tinder box. “Let them eat cake” rarely cuts it as political strategy – government actions to lower food prices are on the rise.

With the brevity of a media digest, but the depth of an intelligence assessment, Daily Assessment goes beyond the news to outline the implications.

Inequalities in and anxieties about food production also play out in international forums.

Poorer countries, typically net importers that are more sensitive to food insecurity and which govern for the lower levels of Maslow’s pyramid, tend to advocate for greater wriggle-room to protect local agricultural interests. Richer countries, especially large food exporters with increasingly heavyset populations, tend to favour free trade.

With minor exceptions, such as the accord reached at last year’s World Trade Organisation ministerial conference, such fundamental divisions between the “Global North” and “Global South” have prevented any global trade deals on agriculture from being agreed over the past two decades. These divisions have also created mistrust, shifted political allegiances and stymied discussions on reforming global governance.

As countries get richer, their food consumption changes. Emerging market countries with growing middle classes hankering for KFC will increasingly start acting like advanced economies on the international scene.

What’s next?

Food insecurity – driven by and driving geopolitical tensions – will only likely increase in coming decades.

The Food and Agricultural Organisation estimates that to satisfy population growth, global food production will have to increase by 60% by 2050. With protectionist impulses unlikely to abate, nations will increasingly do food trade deals with friendly countries and drive up costs. In a world where demand could outstrip supply, competition to produce will intensify – as will pressure to do so in environmentally-friendly ways. Countries able to harness innovation will reap the harvest.

But the many, especially poorer, nations whose food production will be impacted by more frequent climate shocks could also face more frequent political and economic ones. And these, if the Arab Spring is anything to go by, can very easily spread across borders and cause ripple effects.

For business, the geopolitics of food means a world of inefficient and costly global trade, greater risks of political instability in net-importing countries, more interventions in the long and complex global agricultural value chains as governments try to attain greater security of supply, and an increasingly fractured international system characterised more by competition than cooperation.

And it’s happening right now.

Nigeria declared a state of emergency on Friday due to surging food prices. The move will allow for the clearing of forests to increase farm output.

Not a pleasant taste to end on, but food for thought.

We hope you are enjoying Geopolitical Dispatch and, if you are, we would again be very grateful if you could pass it on to a friend or colleague.

Best,

Michael Feller, Cameron Grant and Damien Bruckard, co-founders

Emailed each weekday at 5am Eastern (9am GMT), Daily Assessment gives you the strategic framing and situational awareness to stay ahead in a changing world.