Week signals: Round the mulberry bush

Plus: watch points for the US, Israel, South Africa, India, and Japan.

This week:

IN REVIEW. Sputnik moments, technological firepower, and lessons from the Silk Road.

UP AHEAD. Trump hits a hurdle, Netanyahu goes to Washington, Ramaphosa dismays allies, Dilliwalas head to the polls, and Ishiba does a dance.

The Week in Review: 1,500 years in the chipmaking

The week began with the threat of a US trade war with Colombia. It ended with the threat of one with Mexico, Canada, and China. In between, eastern Congo's largest city was seized, Donald Trump suggested depopulating Gaza, France faced collapse once more, and a tragic crash in Washington encapsulated all that is wrong with US politics (though, of course, nobody can agree on what that is).

Most of all, the week saw a belated but dramatic response to a Chinese AI model developed by a small firm called DeepSeek, which seemingly delivers ChatGPT-level performance for a fraction of the cost. Described by venture capitalist Marc Andreessen as AI's "Sputnik moment", its launch saw $600 billion wiped off Nvidia’s share price in a single day, and panic from Wall Street to Palo Alto.

Insofar as Sputnik shook-up the space race and heralded a shift in power to the USSR, the analogy appears apt. Yet DeepSeek is no product of the Chinese state, nor even one of its major companies. A cheaper version of an existing technology, it is less a demonstration of something the US didn’t have than a clever redesign. Open source, inexpensive, and more than adequate for most users (unless you want to know about Tiananmen Square), a better analogy might be the invention of the Kalashnikov rifle, ten years before Sputnik in 1947 (hence the name AK-47). Today, it remains one of the world’s most popular weapons, used in virtually every warzone, from Ukraine to Gaza.

But unlike a gun, or even a satellite, DeepSeek perhaps mirrors something truer to its name, and, whether Xi Jinping was involved or not, perhaps something also of China’s Belt and Road ambitions.

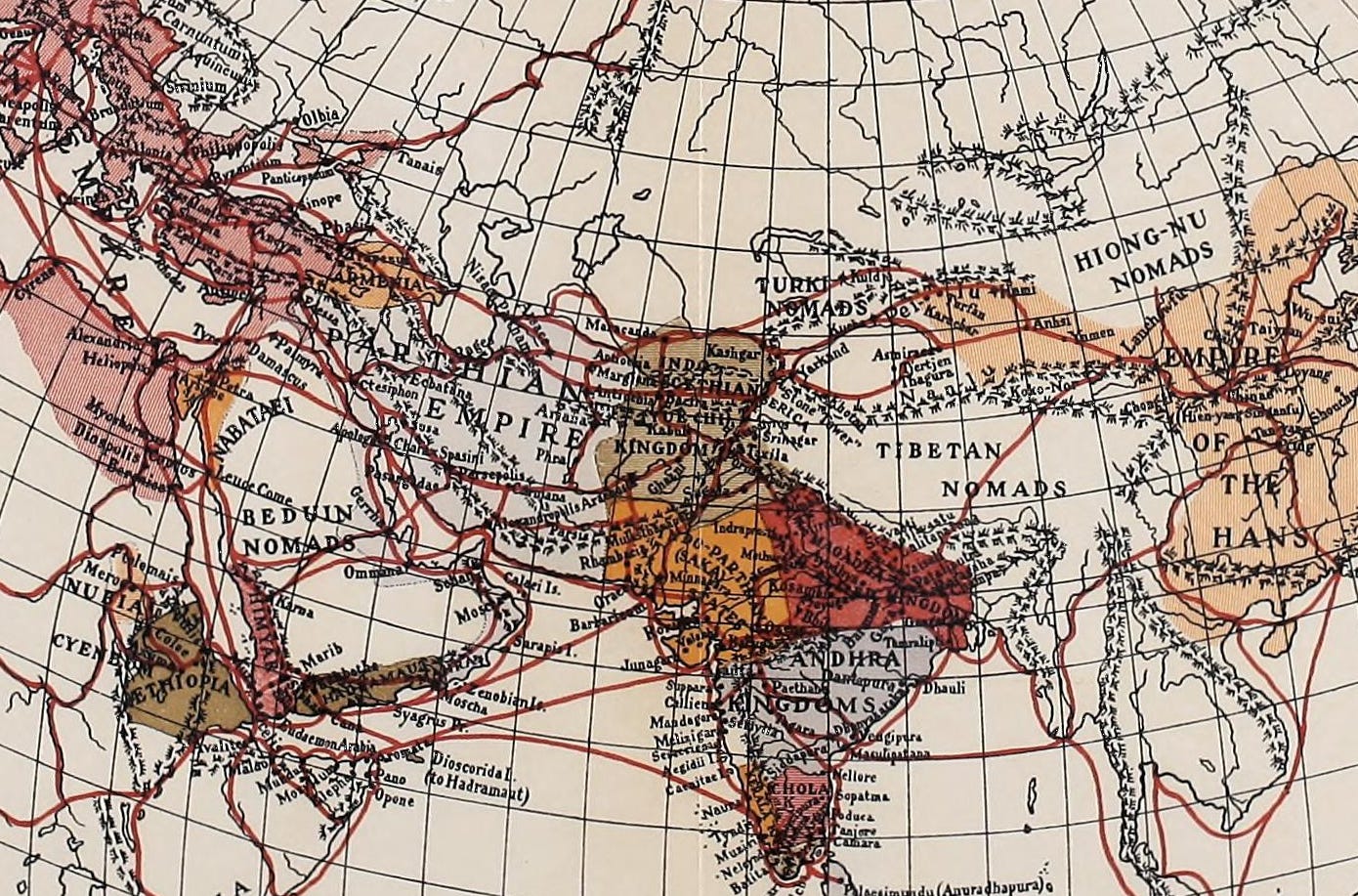

Across much of the ancient world, fashionable people demonstrated their wealth by wearing garments made of silk. Like later European appetites for tea, demand for silk grew so much it began to cause a balance of trade crisis in Rome (which we touched on last week). In 552AD, a solution was found when two enterprising monks offered to bring Emperor Justinian back silkworms and mulberry trees, which they had come across while preaching in the east. The first great case of industrial espionage had thus begun. Over two years, via Transcaucasia and the Caspian Sea, the monks smuggled their cargo in the hollows of bamboo canes. China's monopoly was over. It would remain the world's predominant silk producer (and still is), but soon there would be rivals in Constantinople, Beirut and Thebes.

Operating in a similar IP grey zone, today’s reverse Silk Road transfer may one day be viewed as equally historic – assuming AI (let alone DeepSeek) really is as transformative as many believe. The US may no longer have a monopoly on our era’s most desired technology. Instead, it’s been separated and transferred into a potentially endless number of nodes. And while not all may be as successful as the originating hub (just as China remains the centre of today’s silk industry), the barriers to entry and the costs of production, have suddenly gotten much lower.

This development has other economic and geopolitical lessons too: