Week signals: The blond man’s bluff

Plus: watch points for the Gulf, Nepal, Ghana, Iceland, and the ICC.

This week:

IN REVIEW. The risks of the deal, the irrationality of madman theory, and the escalatory ladder of deterrence.

UP AHEAD. A meeting in Kuwait, trans-Himalayan diplomacy, elections in Ghana and Iceland, and a Roman (statute) assembly.

The Week in Review: The art of coercion

The week began with a surprising election result in Romania and an unsurprising disappointment at COP29 in Baku. It ended with a surprising assault on Aleppo in Syria and an unsurprising breakdown of a truce in Lebanon. In between, the ICC sought a warrant for Myanmar's military leader, rumours surfaced about China's defence minister (followed by the arrest of a more senior military commander), and the Philippines’ vice president threatened to kill her boss.

A more consequential development, however, happened in one of the internet’s darker corners – Donald Trump's Truth Social – where the president-elect threatened new sanctions against Mexico, Canada and China. We’ve been sanguine about their impact, seeing these as a negotiating ploy (as have the counterpart governments), but it raises questions about Trump’s tactics, whether they can be predicted, and whether they may ultimately be self-defeating.

During a long career in real estate, Trump perfected the “art of the deal” his supporters contend. And certainly, his record stands as a tough business negotiator. But as he found in his first term as president, dealmaking in politics, not to mention geopolitics, can differ. In his negotiating style, Trump is known for bluffing. But states generally don’t bluff, as it tends to worsen their credibility over time, an essential factor in the theory of deterrence, compellence, and escalation. And when they do bluff (e.g., Sadam Hussein), the results can backfire.

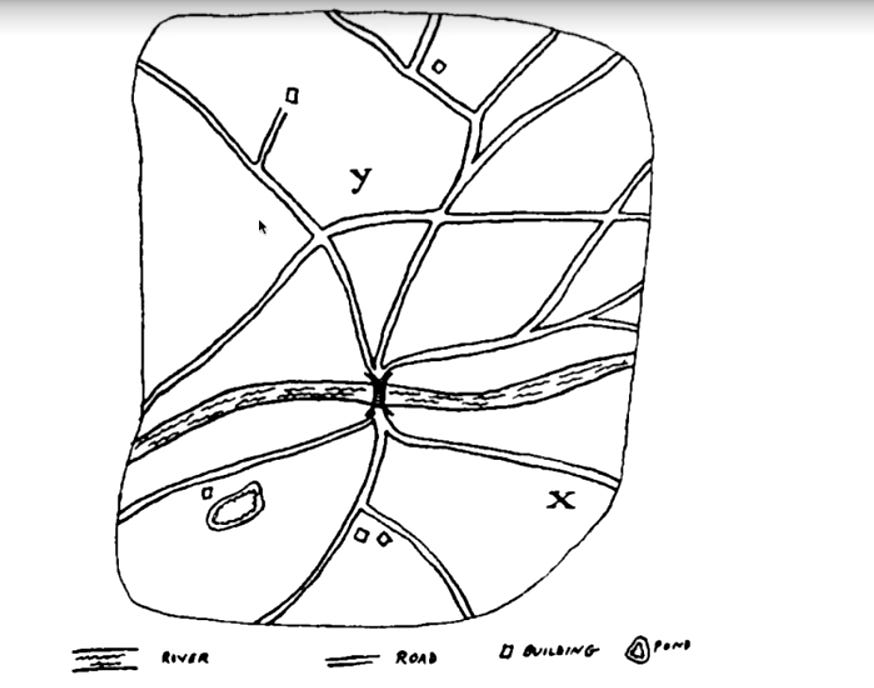

A theorist of geopolitical credibility was the late Nobel laureate Thomas Schelling, who wrote in 1966 that a reputation for resolve "is one of the few things worth fighting over." Trump would probably agree, but where the two might differ is over the problem of coordination (the map here is from Schelling’s 1957 paper on this topic, imagining two people, unknown to each other, parachuting into a landscape and needing to get together to be rescued). To Schelling, the key was the “focal point” (Grand Central Station is the classic example in everyday life – if you’re ever lost in New York). In diplomacy, it’s “each person’s expectation of what the other expects him to expect to be expected to do.”

The idea isn’t unknown in business – traders like George Soros built fortunes atop the similar concept of reflexivity – but as businesses generally don’t go to war (in the most meaningful sense), and as deals are usually finite, or finite in number, they tend not to experience the full impact of a bluff gone wrong, or a decline in credibility. States, whose interests tend to be more permanent and whose games, or deals, tend to never end, prize credibility above all else.

Schelling, who passed away in December 2016, a month after Trump’s first election, was also a proponent of the “madman” theory of diplomacy. Here, Schelling understood “the power to hurt is bargaining power”, but he also knew a small threat can be greater than a bigger one (he gave the analogy of two people competing for a prize, chained at the ankle and standing at a cliff, wherein the correct strategy would be dance closer and closer to the edge, convincing the other you're completely irrational). So far so strange (or Strangelove – Schelling was also an adviser to Stanley Kubrick), but if this “strategy of ambiguity” veers too obviously into the strategy of blackmail, will the bluffs work?