Week signals: The young and the leftward

Plus: watch points for Cambodia, Syria, Iraq, India, Kazakhstan, and Russia.

Hello,

In this week’s edition of Week Signals:

IN REVIEW. Counterculture in the 21st century, the world according to Gen Z, dynasty vs destiny, moral rotation.

UP AHEAD. Southeast Asian borders, Mesopotamian intrigue, Bihar’s election, and Silk Road hedging.

And don’t forget to connect with me on LinkedIn.

Week Signals is the Saturday note for clients of Geopolitical Strategy, also available to GD Professional subscribers on Geopolitical Dispatch.

The Week in Review: Talkin’ ‘bout their generation

The week began with Donald Trump threatening to invade Nigeria. It ended with an offer to exempt Hungary from Russian sanctions. In between this bait-and-switch, however, a more consequential trend took another step: the global Gen Z revolt arrived in New York with the election of Zohran Mamdani as mayor.

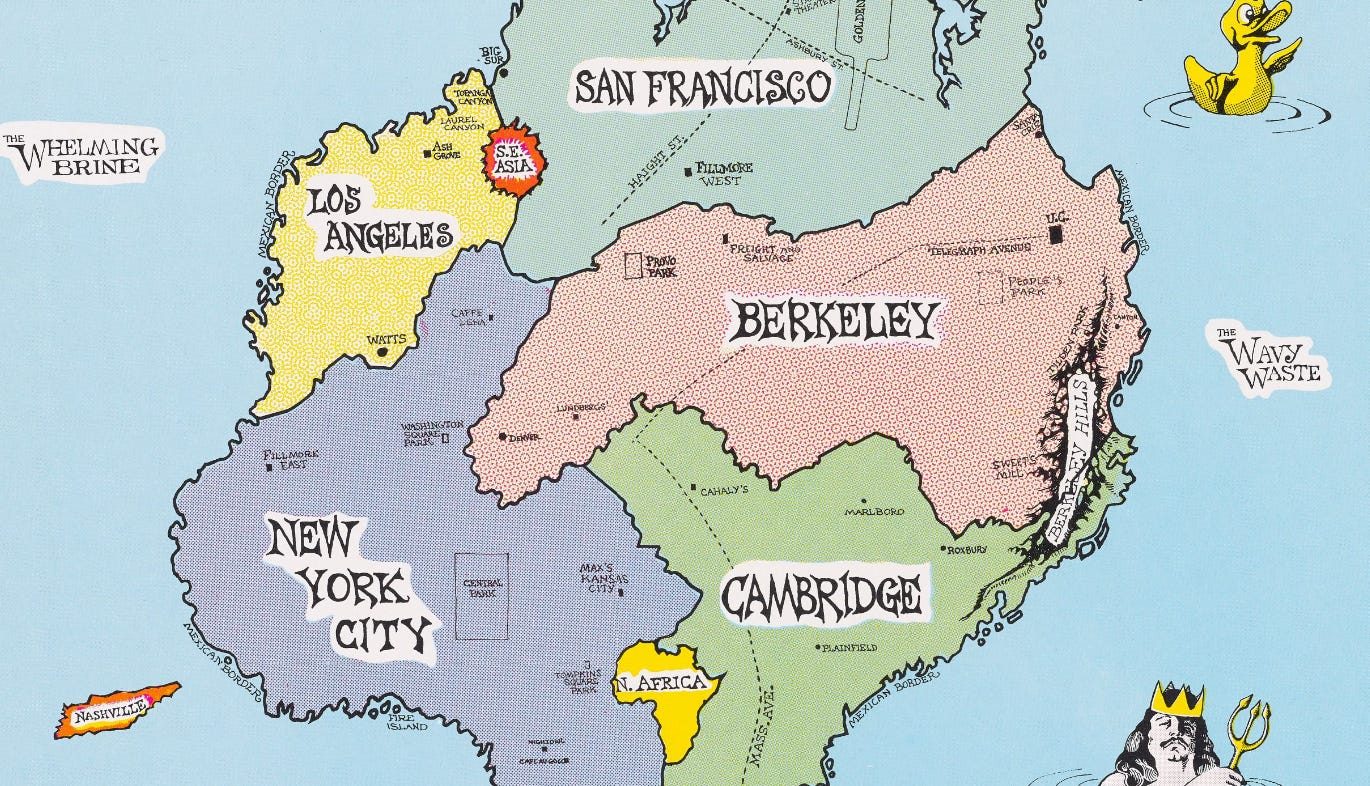

From Cameroon to the US, the world is run by old men (and a few old women). Most are from the senior end of the Baby Boomer demographic (1946-1964). These older boomers, who came of age during an unprecedented economic flourishing (at least in the West), styled themselves as a generation that would break from its past. And they did. Not only were they a particularly large cohort — the consequence of pent-up household formation in the wake of World War II — but they emerged in a completely different technological, political, and social order than their parents (another consequence of the war). Thus while the world of 1968 – this generation’s cultural apex – saw the election of arch-conservative Richard Nixon in the US and the Invasion of Czechoslovakia under Leonid Brezhnev in the USSR, it is best remembered today for what it would later portend: the era of civil rights; the youth-led protests of Paris and Chicago; the culture-shifting impact of television media, particularly the Apollo 8 ‘Earthrise’ shot and the ‘And babies’ photo of the My Lai massacre; the music of Jimi Hendrix, the Doors, and Pink Floyd.

The year 2025 may be remembered similarly. While it began in a reactionary fashion – the end of pronouns and the return of Donald Trump – for much of the world, there’s been a 1968, if not 1848, energy. In the wake of Bangladesh and Sri Lanka, governments have fallen in Nepal, Madagascar and Peru, after youth-led protests. That cohort – Generation Z or Zoomer – like their boomer grandparents now in charge in the West, is the largest cohort in those countries. And like generations before them, it has been inculcated on new media (TikTok vs TV), new technological realities (AI vs automotive), and new economic and social anxieties that older leaders aren’t addressing and possibly don’t even understand.

Zoom out, as it were, to New York, and a similar trend is underway. Mamdani has been described in much of the press as a chancer (went to preppy Bowdoin College) and a flash in the pan (a mayor can’t do much anyway), but he appears authentic and, winning 78% of the 18-29 vote, he can’t easily be ignored. Like all politicians, he may not be able to implement all the policies he campaigned on, but he has injected a new energy and a new statist vision of what American government could be – a vision that hasn’t been this mainstream since perhaps the 1930s. While not discarding the identity concerns of the Biden-Harris Democratic Party, he has pivoted hard to a self-described socialist agenda, focused squarely on working-class voters, whom Trump has otherwise courted in increasing share until now. A heady combination of cost-of-living anxiety with youthful utopianism, it’s the kind of movement that could not just be competitive at next year’s midterms, but completely crush the GOP.

A fortnight ago, we wrote about the potential for a counter-counterrevolution in US politics as Trump transits the “J-curve“ of authoritarian governance. A few weeks earlier, we wrote about the clash of geopolitics and ‘demo-politics’ seen in the emerging world’s Gen Z protests. This week, it’s time to examine the potential effects of this dynamic in the developed world, which is much older, more boomer-centred, and more ideologically messy, insofar as the direction appears to be of political fragmentation, than the subaltern cohesion that leads to successful regime change. So is Mandami on the vanguard, or is he on the fringe? Will this year be a 1968 in terms of portending a generational shift, or an 1848 in terms of a failed revolutionary experiment? What should businesses and investors watch for as they try to gauge whether the US is heading ever rightward, or back to FDR-style democratic socialism?

Mamdani’s election, for all its local colour and idiosyncrasies, such as free buses, is a window into a deeper realignment already underway across the advanced economies. The story is demographic before it is ideological. The median age of the US is now roughly 39; in Europe, closer to 44; in Japan, nearly 50. Yet within those aggregates sits an inversion of political power and cultural energy. The old own the assets, run the institutions, and dominate the vote; the young occupy the service jobs, shoulder the debts, and populate the streets. For a decade, this imbalance has generated frustration without an outlet. Now, as the economic consequences of ageing societies collide with the technological consequences of AI and white-collar automation, the young are beginning to articulate a new political language, which blends a moral urgency with economic grievance, and a utopian internationalism with parochial rage.

This language is not confined to New York. In London, student-led rent strikes during Covid-19 have solidified into neighbourhood campaigns for municipal ownership of housing. In Berlin, the Enteignen (expropriate) movement, which peaked a year or so later, continues, arguing that the only way to fix the housing market is to nationalise it. In Paris, the post-Mélenchon left has reconstituted itself as a coalition of eco-socialists and anti-imperialists, giving a once-youthful Emmanuel Macron an existential headache, and drawing its moral vocabulary as much from the Global South as from the French labour tradition. These are not coordinated movements, and vary in sophistication and coherence. But they share a tone, which is impatient, globally literate, and allergic to the hypocrisies of what they see as late-stage liberalism — a political order that has long promised opportunity while delivering precarity.

In the US, this tone is amplified by the country’s unique demographics. Millennials and Gen Z now make up a majority of the workforce, but still control less than 10% of total wealth, depending on how you measure it. Their parents’ Gen X generation had achieved that level of affluence by the time they were thirty. A decade of asset inflation, wage stagnation, and pandemic whiplash has produced what economists call “declining birth expectations” — the quiet decision by millions of young adults not to have children because they can’t afford to. It is the single most important long-term signal for investors: fertility is the ultimate forward indicator of confidence. When it collapses, it doesn’t just shrink future labour pools; it signals that the social contract itself is fraying.

The political consequences now appear to be catching up. Mamdani’s victory could be less a left-wing anomaly than the early symptom of a generational convergence: younger voters, including many from the political centre and even the libertarian right, are turning toward state intervention, not because they have suddenly fallen in love with government, but because the market has failed them. The gig economy, once sold as liberation, has matured into a trap; the housing market is structurally exclusionary; education is increasingly priced as a luxury good. The result is a constituency that no longer believes in incrementalism.

It is fashionable to describe this as populism, and in some ways it is. But it differs sharply from the nationalist populism of the 2010s, which culminated in Brexit and Trump. The Mamdani generation does not dream of anti-globalist sovereignty; it dreams of anti-capitalist fairness. It is animated less by nostalgia than by exhaustion — a quiet fury at being asked to play by rules written for a different century. That distinction matters. Where Brexit and Trump channelled resentment into cultural war, this new current channels it into structural critique: of landlords, monopolies, and energy companies; of the political capture of ageing democracies by those with assets to defend rather than futures to build. Watch Mamdani’s acceptance speech, with its critique of Trumpian developers, to understand.

If this sounds radical, it is also recognisably cyclical. Every long boom ends with a politics of redistribution. The Industrial Revolution produced social democracy. The post-war boom gave rise to the welfare state. The neoliberal boom — the one now ending — produced the asset economy and the politics of tax revolt. As that order decays, it is natural that its successor will reach again for solidarity, for the state, for collective insurance against a volatile world. Whether this will take the form of a disciplined New Deal-style reformism or a chaotic new left is the question of the decade.

For business and investors, the implications are profound. The next political economy of the West is likely to be more regulated, more redistributive, and more moralistic. We are already seeing this in nascent form: industrial policy disguised as climate action, competition policy disguised as national security, and taxation framed around fairness (cf Rachel Reeves’ recent pre-budget address on Downing Street). A Mamdani administration in New York will not itself set global fiscal trends, but it will signal where the moral energy of the young is flowing — toward using the state not as a brake on capitalism but as a lever to reset it. Expect the language of “public options,” “stakeholder rights,” and “post-neoliberal capitalism” to move from the think-tank fringe into general discourse. Expect investors to begin factoring political legitimacy into valuation models, not as ESG window-dressing but as real regulatory risk.

There are other signals to watch. One is the behaviour of the tech sector. Silicon Valley has long been an early detector of ideological shifts because its labour force skews young and its business model depends on sentiment. Over the past year, a subtle reversal has begun: workers are unionising, and the cultural cachet of tech bro “founder freedom” is fading. The narrative is shifting from disruption to duty — from the hacker to the steward. That inversion, if it continues, will have effects far beyond tech: it will shape the future of capital allocation, the rhetoric of leadership, and the willingness of governments to subsidise innovation without demanding social dividends.

Another signal lies in the politics of ageing. For decades, ageing populations have been treated as a fiscal problem: too many retirees, not enough taxpayers. But the politics of intergenerational transfer are becoming harder to ignore. Pensions, healthcare subsidies, and property-linked tax breaks now represent an implicit redistribution upward, from young to old. The moment that dynamic becomes visible, it becomes unsustainable. Watch for early signs in local referendums and ballot measures — property-tax reform in California, inheritance-tax debates in the UK, long-term-care funding in Japan. These are the tripwires of generational politics.

And then there is immigration. As birth rates fall and labour shortages intensify, Western economies will depend more on migration even as their electorates grow more divided over it. The young tend to see immigration as an opportunity, the old as a threat. Politicians who can bridge that divide will define the next era of centrism — if centrism survives at all. The risk for investors is that immigration policy becomes the new battleground for inflation control, with governments alternately opening and closing the tap of labour supply in response to short-term price pressures.

Underpinning all this is the slow but inexorable decline of institutional trust. Surveys across the OECD show record-low confidence in legislatures, the mainstream media, and big business. The vacuum this creates will be filled not by technocrats but by movements — fluid, moral, sometimes incoherent, but capable of seizing viral moments. The Mamdani phenomenon is one such moment: a reminder that legitimacy in politics, as in markets, is a confidence game. When confidence evaporates, so does deference.

Yet it would be a mistake to see this purely as a revolt of the young. Demographics are destiny only when they align with narrative. What is changing is not merely the age profile of electorates but the meaning of progress itself. For two generations, progress was defined as efficiency: faster growth, cheaper goods, more convenience. The emerging generation defines it as stability: predictable rent, decent work, a liveable planet. That shift — from acceleration to repair — will reorder the hierarchy of economic virtue. Firms that promise safety, reliability, and purpose will likely outperform those that promise speed, scale, and disruption.

For all the noise of daily politics, then, the deeper story is one of moral rotation. Each era selects its own virtues. The coming one is likely to reward patience over ambition, equality over aspiration, the public good over private gain. That may sound sentimental, but markets are already adjusting: witness the rise of “slow growth” portfolios, the premium on local production, and the renewed appetite for public ownership of strategic assets. These are not ideological accidents. They are the first outlines of a new political economy being written, as always, by demographics before doctrine.

Whether Mamdani himself endures is beside the point. Like the protests of 1968, his victory is less important as a policy event than as a cultural signal that the next generation has found its vocabulary. Investors should listen closely, not because socialism is suddenly back, but because its broader sentiment is. In politics as in markets, conviction is the most valuable commodity, and it has clearly shifted to the young and the leftward.

The Week Ahead

CAMBODIA. Watch for intransigence

On Sunday, Cambodia marks its first independence day since its brief war with Thailand over their historically contended border region. A ceasefire negotiated by ASEAN and claimed by Donald Trump is holding but ill-will toward Bangkok holds and Hun Manet will want to bolster his reputation among nationalists. Hun, son of former prime minister Hun Sen – who exacerbated the crisis when he leaked a call with Thailand’s then-prime minister, another dynast, Paetongtarn Shinawatra – has been blamed for governance declines and the capture of the state by organised crime (notably the multinational Prince Group, charged by Western governments with running massive online fraud operations). He recently rejected offers from Thailand to help in fighting the scammers.

SYRIA. Watch for the limits of pragmatism

On Monday, Donald Trump will host Ahmed al-Sharaa, Syria’s new president, who has recently had sanctions removed from his days as an Al Qaeda commander. Sharaa has achieved a remarkable public image turnaround, at least in the West, for his pragmatic engagement and overt preferences for technocratic government. But looking better than predecessor Bashir al-Assad is a low hurdle and Sharaa could soon face opposition from the Sunni majority, not just minority groups, should life not improve in tandem with his controversial outreach to the US, Russia and even Israel. Sharaa has faced such pressure before, when, as de facto head of the then Syrian Salvation Government in Idlib, he had to be rescued by Turkey. That may happen again if his deals with Trump promote a public backlash.

IRAQ. Watch for Iranian tenacity

On Tuesday, Iraqis will vote in parliamentary elections. Incumbent Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani’s Reconstruction and Development Coalition is expected to be returned in alliance with several of the competing Shia-dominated parties that have fractured in recent years but still provide Iran with a quiet but genuine sway over Iraq. These parties, and the militias that back them, have stayed out of the Iran-Israel war but this does not diminish Tehran’s influence across Iraqi society and the economy. Reasonably good relations with the West should also not be mistaken for allegiance. Iraq’s current and next government may not overtly help Iran but it could still covertly work to keep it in business.

INDIA. Watch for a bellwether

Also on Tuesday, Bihar will hold the second phase of its legislative elections (the first was on Thursday). India’s second largest state, with 131 million (more than Mexico or Japan), is among its poorest, and has a nominal GDP barely the size of Ecuador. Yet politically, Bihar is less a laggard than a bellwether for the role of religion and caste in an evolving political system. Seen as a test for Narendra Modi, the results, due to be released on Friday, will greatly shape how elections in the largest state, Uttar Pradesh, are prepared for in 2027. At a national level, Modi’s coalition partners Janata Dal and Lok Janshakti, also provide supply in Bihar (Janata Dal’s Nitish Kumar is Bihar’s current chief minister). A loss for Janata in Bihar could lead to cracks nationally and impact the stability of Modi’s government.

KAZAKHSTAN. RUSSIA. Watch for equivocation

On Wednesday, Kazakhstan’s President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev will meet Vladimir Putin in Moscow, a week after meeting Donald Trump in the White House. The two leaders, both former Soviet operatives (Tokayev in the foreign ministry; Putin in the KGB), have known each other professionally since the late 1990s and, as with their countries, the links between them go far deeper than those with Trump or the US. They most recently met in Tajikistan and contact is frequent. Still, the Washington trip will have concerned Moscow, ever vigilant about its declining influence in its near-abroad. As in Soviet times, Moscow will want visible signs of ongoing Kazakh loyalty, but Astana will want to demonstrate its growing independence, which Tokayev has accelerated since an attempted putsch of 2022.

Thank you for subscribing to Geopolitical Dispatch. Feel free to contact me with any questions or comments.

Best,

Michael Feller, Chief Strategist

michael@geopolitical-strategy.com

This briefing is for general information only. It is not legal, financial or investment advice. Information and opinions are current at the date of publication and are subject to change without notice. There is no representation or warranty as to its accuracy, completeness or reliability, and no liability for any loss arising from use or reliance on this information is accepted.