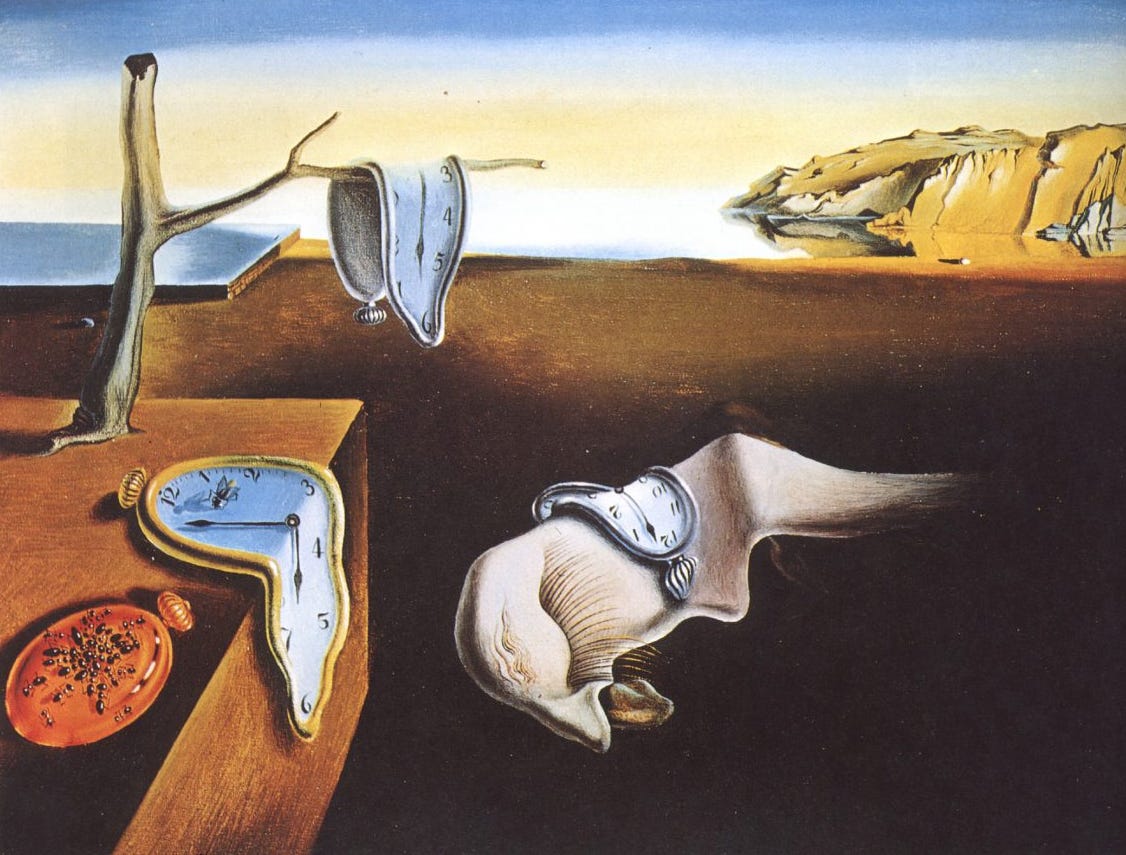

Year in Review: In search of last time

A remembrance of a transformative year.

The year began with wars in Gaza and Ukraine, four new BRICS members, an election in Bangladesh, an Islamic State attack in Iran, and a crisis in Somalia. It ended with wars in Gaza and Ukraine, upsets for BRICS members Iran and Russia, a coup in Bangladesh, Syria’s takeover by an ex-Islamic State militia, and a resolution in Somalia.

In between, Israel wiped out Hezbollah, South Korea declared martial law, and floods hit Europe, Brazil, East Africa, and the Gulf. Meanwhile, Donald Trump was elected, Sweden joined NATO, and Iran's president was killed. Elsewhere, coups were tried in Bolivia and Congo, and democracy was quashed in Pakistan and Venezuela.

How does one define such a year? For many, it was the US election. For others, it was an anti-incumbent wave that saw, among others, governments also lose power in Britain, France and Senegal, as well as majorities in India, Japan and South Africa. And then there were the markets (bitcoin, AI, meme stocks), tech (drones, spaceflight, quantum computing), and culture (the Olympics, TikTok, Taylor Swift).

In the absence of an easy definition, many have made comparisons to other years to spot the broader trends. The most common has been 1968 – the year of Nixon’s election, the Apollo 8 lunar orbit, MLK’s assassination, and student protests. Comparisons have also been made to 1848 – a similar year of revolution and technological change – and to 1938, albeit largely to suggest that 2025 will be like 1939.

Yet for us, our search for a more meaningful comparison arrives at another period altogether. Like 2024, it was less a moment of sudden revolution than of ongoing transformation. And unlike 1968, or 1848 – false dawns that otherwise failed to shift the global order – it wasn’t so much dramatic as seismic, where conditions were set for more visible changes to follow.

We’ll cover those changes next week – in our forecast of 2025 and review of last January’s predictions – but for now, let’s go back in time to examine what in our view is 2024’s nearest parallel.