Irregular: On thin ice

How Europe should respond on Greenland

Hello from Melbourne,

Today’s Irregular will live up to its title.

We do not ordinarily offer advice, at least in Geopolitical Dispatch. Its purpose is to orient readers to the world as it is, not to prescribe how governments should behave. Analysis, properly understood, clarifies choices rather than making them. But there are moments when refusing to draw conclusions is itself a form of evasion, e.g., when neutrality becomes a way of avoiding the implications of power.

Europe now faces such a moment.

The United States is threatening a European state with economic coercion in pursuit of territorial acquisition. It has refused to rule out the use of force. That combination — territorial demand, coercive pressure, and strategic ambiguity — forces a reckoning that Europe can no longer postpone, even if many believe, or at least hope, that this is merely Trump’s art of the deal, or something that will ultimately be TACO’ed away.

But the question Europe must answer is not whether this behaviour is wise, legal, or normatively acceptable. Those questions are largely settled. The real question is whether the threat is real, and, if it is, what Europe is prepared to do about it.

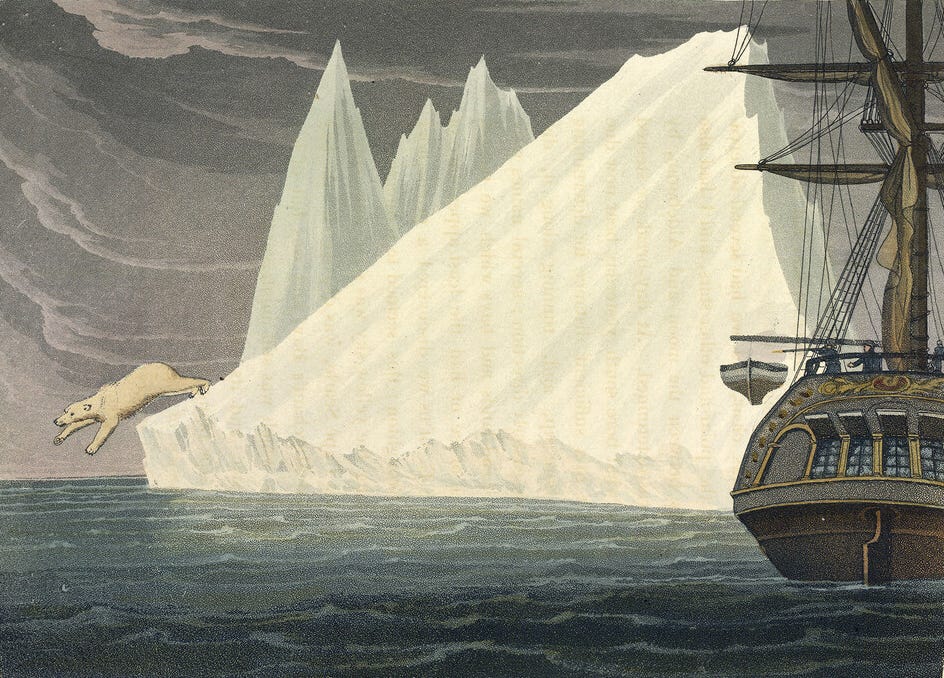

How much can a polar bear?

The President of the United States has stated repeatedly and unequivocally that he wants Greenland.

These statements have not softened with time; they have intensified. What began as rhetoric has hardened into insistence. That insistence has been paired with explicit threats of economic punishment directed at Europe and Denmark in particular. Tariffs are currently the means — instruments of political pressure designed to compel acquiescence — not the ends. And it would be a major mistake to view them as the end goal.

Most significantly, the President has declined to rule out the use of military force.

In statecraft, this matters more than tone, legality, or even credibility in the narrow sense. Strategic ambiguity is not an accident. It is a tool. Refusing to deny the use of force shifts the burden of risk onto the other side. If Europe assumes bluff and is wrong, it confronts irreversible facts. If it assumes seriousness and is wrong, it still pays a cost, but one that is finite and reversible.

Much commentary has focused on whether this demand is “rational.” Analysts point to the absence of an obvious strategic necessity, the weakness of arguments about protection or security, and the diplomatic costs involved. This line of analysis misses the point entirely.

International politics does not turn on whether motives are elegant or well-reasoned. It turns on what leaders want, how strongly they want it, and whether they believe they can obtain it at an acceptable cost. History is full of territorial acquisitions driven by vanity, symbolism, domestic politics, or personal obsession rather than tidy strategic logic. A fixation on acquisition does not require a coherent doctrine to be dangerous.

What matters here is simple: the demand exists, the pressure is escalating, the option of force has been left deliberately open, and the US has begun to prepare its specialist Arctic forces for deployment – even if, for now, apparently to Minnesota, as Michael wrote today.

If Putin had repeatedly expressed a desire to annex Greenland, offered strategic rationales, asserted the land lay within “its” rightful hemisphere, made the argument that the local population wanted to join Russia and required its protection, ordered Russian Arctic military forces to deploy to a temperate region to quell domestic crime, no one would be debating whether he was serious or assuming that his end goal was simply a 10% tariff hike.

We’ve seen this movie before.

Geopolitical Dispatch is a daily strategic briefing for business leaders and investors, based on the US Presidential Daily Brief. Covering five top global developments at 5am Eastern Time, Geopolitical Dispatch gives you visibility of events in context.

You don’t have the cards

Trump’s self-proclaimed mastery of deal-making makes people assume he is only ever after a deal. A businessman and even a showman, but not an imperialist. But this is not a negotiation in the ordinary sense. It is an exercise in what Thomas Shelling called “compellence” (see our analysis on this concept from 2024).

Economic pain is being applied not to extract concessions within a shared framework, but to force a political outcome the target explicitly rejects. The tariff schedule is not about revenue. It is about signalling: compliance will be rewarded with relief; resistance will be punished. The refusal to rule out force is the final layer of pressure, and a reminder that economic coercion is not the ceiling.

This is how coercion works. The threat need not be certain. It need only be plausible enough that the costs of miscalculation appear intolerable. Ambiguity is not weakness; it is leverage.

The danger for Europe lies in misreading this as theatre. Coercion succeeds when the target convinces itself that escalation is unthinkable, that the coercer “would never really do it,” and that accommodation will restore normality. It rarely does.

No eternal allies, no perpetual enemies

The argument that this threat should be treated as credible derives from consistently observed behaviour over the past year.

First, the use of force in the Western Hemisphere has been normalised in cases where traditional national security rationales were contested or thin. Military action has been undertaken not only where existential threats were clear, but where political objectives were framed expansively and opportunistically. The lesson is not about any single operation; it is about the lowering of psychological and political barriers to using force as a policy tool.

Second, alliance commitments have been increasingly treated as conditional and transactional. Public statements questioning the automaticity of defence obligations, and framing protection as something to be earned rather than assumed, fundamentally alter the meaning of alliance. Once commitments become contingent, they cease to deter in the traditional sense. They become instruments of leverage rather than guarantees.

Third, the Greenland episode itself has escalated rapidly. What might once have been dismissed as provocation has triggered emergency discussions in European capitals, mobilisation of economic countermeasures, and explicit planning for retaliation. Institutions do not behave this way unless they sense that something structurally different is occurring. This is not routine trade friction. It is coercion touching sovereignty.

Taken together, these patterns matter more than any individual statement. They indicate a willingness to press advantage, to test taboos, and to see how far pressure can be taken before resistance materialises.

It is a mistake to treat this as a narrow dispute about a remote, sparsely populated territory. The strategic significance lies not in Greenland itself, but in what success or failure would demonstrate.

If coercion succeeds here, it would show that sovereignty inside the European political space is conditional when confronted by sufficient pressure. It would demonstrate that economic pain can substitute for consent. And it would fracture the assumption — central to Europe’s post-war order — that borders within the alliance are inviolable.

If it partially succeeds — through hesitation, quiet bargaining, or symbolic concessions — it still weakens Europe. It teaches that unity can be strained, that resistance is negotiable, and that pressure pays.

This is why the issue cannot be compartmentalised. Greenland is a test case of cohesion, of resolve, and of whether Europe still believes in the basic logic of statehood.

Only perpetual and eternal interests

Stripped of sentiment and habit, Europe’s interests form a clear hierarchy.

First is territorial integrity. Greenland is part of the Kingdom of Denmark. Denmark is a European state. For absolute clarity: a foreign power is threatening to acquire European territory against the will of its sovereign government. The size, climate, history, location, or population of that territory is irrelevant. The primary function of any political community is to defend its territory. If that principle fails, all others become contingent.

Second is resistance to coercion. Denmark has decided it does not wish to relinquish Greenland. Europe has a vital interest in ensuring that no member state is forced to surrender territory under economic or military pressure. Yielding once guarantees future demands, whether from the same actor or others watching closely.

Third is precedent control. Europe cannot permit the forcible annexation of European territory by any external power. This principle is more foundational than any of Europe’s external commitments, because it concerns the integrity of its own political space.

Fourth is the preservation of European cohesion. Foreign pressure designed to fracture the Union must be resisted. The future of the European project is a matter for Europeans alone. Its cohesion is also essential for managing other external threats, including those that remain closer to Europe’s borders.

Finally, Europe has an interest in ending its vulnerability to bullying. A continent that can be coerced over Greenland can easily be coerced elsewhere, whether on trade, technology, regulation, or security.

There are, of course, countervailing considerations.

Avoiding military conflict with the United States is, of course, a profound interest. The imbalance of power is real. Any confrontation would be dangerous, destabilising, and economically costly. It would almost certainly spell the formal end of existing alliance structures and force Europe into a rapid, painful transition toward strategic self-sufficiency. F-35s would fail to launch. The nuclear umbrella would dissolve into air.

But such objections cut both ways. Alliances are sustained by trust and good faith. A security guarantee offered by a state that threatens its allies’ territory, whether in jest or in seriousness, is already hollow in substance, even if it persists in form. An alliance that cannot survive a dispute over sovereignty is an illusion maintained by habit rather than belief.

Economic considerations also matter. Tariffs, sanctions, and financial coercion would impose real costs on Europe. But economics has always been secondary to sovereignty. States that invert that ordering tend to lose both. Prosperity purchased at the price of territorial integrity rarely endures.

Greenland is not Paris or Berlin. But it is still European territory. A Europe that draws its red lines only where it is comfortable will soon find it has none.

Cold comfort

If Europe takes its own interests seriously, several conclusions follow. They are uncomfortable, but unavoidable.

First, Europe must be prepared to defend its territory even against the United States. If foreign forces land on Greenland without Danish consent, Europe must be willing to use force. Anything less is not defence but performance. Deterrence fails when an adversary believes resistance will not occur.

Second, Europe must be prepared to accept the end of existing alliance arrangements if such an event occurs. In truth, NATO may already be dead. An alliance without trust, or one that collapses the moment sovereignty is tested, is not an alliance; it is a legal relic.

Third, Europe must act now to change the adversary’s calculus. At present, the assumption in Washington is likely that Europe will protest, negotiate, and ultimately accommodate. That assumption must be broken before it hardens into action. This requires visible unity, credible defensive preparations, and unambiguous signalling that the costs of coercion will be real and enduring.

Fourth — and most controversially — Europe has an interest in the end of a political regime in the United States that is willing to threaten European sovereignty. This is not a moral judgement. It is a strategic assessment. And we would say the same if the shoe were on the other foot. Trump’s convergence of power, ideology, and willingness to break taboos cannot be assumed to self-correct. Economic pressure that creates domestic costs may both deter escalation and shorten the lifespan of a hostile posture.

This brings into view the most extreme economic instruments: exclusion from critical financial infrastructure (e.g., SWIFT), the removal of sovereign wealth ($10 trillion of it), or denial of access to essential technologies (ASML chipmaking equipment that America’s AI economy relies on). These are not ordinary tools. They would provoke retaliation and carry enormous systemic costs, including to Europe. They are closer to economic warfare than diplomacy.

But their very extremity is the point. Only measures that threaten core interests alter great-power behaviour quickly. The danger lies not in recognising this, but in threatening such measures without the willingness or capacity to follow through.

The risks of this course are obvious: economic disruption, market instability, escalation through miscalculation, and internal European division. These risks are real and should not be minimised.

The benefits are equally stark: preservation of sovereignty, deterrence of future coercion, and the transformation of Europe from a reactive object into a strategic actor capable of self-preservation.

The greatest danger lies not in escalation, but in hesitation. A Europe that signals uncertainty invites pressure. A Europe that signals resolve may avoid conflict altogether. Coercion thrives on doubt, not on strength.

New subscribers are eligible for a 50% introductory rate for the first year. You can decide over time whether receiving all five daily briefs, five days a week, earns a permanent place in your routine.

Final judgment

Europe is not being tested over Greenland. It is being tested over whether it still believes in the elementary logic of statehood.

If Europe cannot defend the territory of one of its members against coercion by any power — even a longstanding ally and protector — then the European project has already failed, regardless of what institutions remain standing.

The objective is not to defeat the United States. It is to convince it — clearly, early, and irrevocably — that Europe will not yield and the costs of continuing will be unacceptable.

That is the logic of this moment. And it is, as Trump knows, and whether Europe likes it or not, the logic of power.

Best wishes,

Damien

This is why Canada turned to China from my view

The Great Northern Asphyxiation: Why Canada is Mathematically Bound to the East

Beyond Ideology: The Geometric Necessity of the "Sino-Canadian Pivot" in an Age of Arctic Enclosure.

https://whisperedyangwenli.substack.com/p/the-great-northern-asphyxiation-why