The geopolitics of Turkey

A primer for after Thanksgiving.

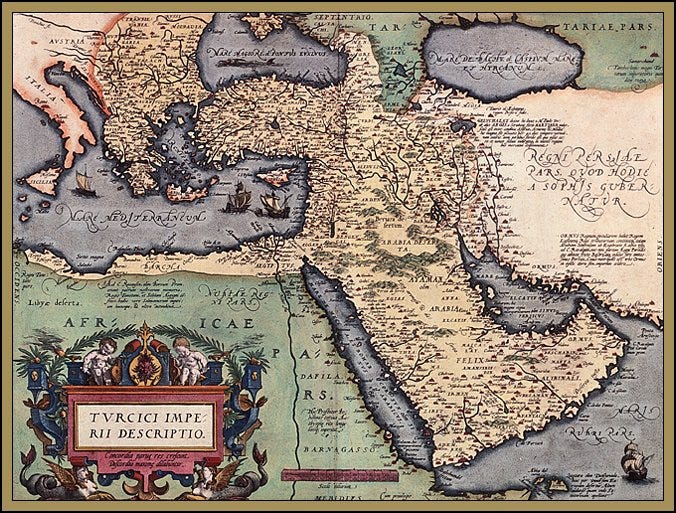

Welcome to a special edition of Not in Dispatches in honour of Thanksgiving on Thursday - our best Turkey recipe, examining the country’s foreign policy. (And at the end of today’s essay, you can read the result’s from last week’s poll on China and Taiwan.)

Location, location, location.

A former ambassador to whom one of us worked in Moscow once said that, to understand any country’s foreign policy, you must understand its geography, its geology and its history.

The effect of geography on Turkey is especially powerful.

At the crossroads of Europe and Asia, Turkey - or Türkiye to its friends - acts as the proverbial bridge between East and West. Consequently, it plays a strategic role in both regions. And Turkey’s foreign policy often revolves around balancing its interests in the “world heartland”.

Turkey is bounded on the north by the Black Sea and on the west by the Mediterranean and Aegean, both major shipping routes. It has control of critical waterways through the Bosphorus Strait and the Dardanelles - as well as obligations under international law to keep traffic open.

Turkey shares land borders with Georgia and Armenia (on the northeast), Azerbaijan and Iran (on the east), Iraq and Syria (on the southeast) and Greece and Bulgaria (on the northwest). Many of these frontiers have seen significant conflict in the previous decade and some are home to Kurdish separatists, terrorist threats (both Western-defined ISIL and Turkish-defined PKK) and significant refugee flows. Turkey hosts more refugees than any other country - 3.4 million of these are Syrian - and the desire to avoid hosting any more influences its policies in Syria as well as with Russia.

Turkey’s geography makes it a natural transit stop for energy. Situated between the oil-rich areas of the Middle East and the Caspian basin, and the energy-consuming markets of Europe, Turkey has become a middleman for fossil fuels, especially natural gas. It is also home to a tangle of cross-border pipeline connections.

In recent decades, Turkey has amped up its transit ambitions, opening new infrastructure such as the TurkStream pipeline from Russia (its third from that country), and the Trans-Anatolian pipeline from Azerbaijan.

Turkey’s geology has recently begun to offer benefits too, with new fields starting low-level production – about three per cent of domestic consumption – in 2023.

But until (or unless) production increases, Turkey will continue importing almost half of its energy from Russia and around 10% from Iran, which is a dependence that shapes its diplomatic relations with both nations.

And while geologists believe, and sometimes politicians proclaim, that Turkey is home to the “rare earths” and “critical minerals” essential to the modern global economy, few have been found or made it out of the ground. That said, Turkey does have 73% of the world’s elemental boron reserves, mostly untapped, and refines about 50% of global boron supply.

Back to the future.

Turkey’s history also shapes its foreign policy.

Most prominent is the legacy of the modern state’s founder, Mustafa Kemal ‘Atatürk’. His alignment with Western values, for example, persisted through subsequent ‘Kemalist’ governments, leading to Turkey’s early membership of NATO (1952) and later its aspirations to the EU.

His state policy of secularism was also retained, which let Turkey avoid the sectarian squabbles common in the Middle East and maintain a balance of relations with both Western and Muslim countries. Yet the Kemalists were also responsible for Turkey’s uncompromising brand of nationalism, under which Greeks, Armenians, and Jews were driven out, and millions of Kurds banned from so much as speaking their own language until 1991 (it is still illegal as a language of instruction).

There are obvious implications for Turkey’s rapport with Greece and Armenia in this history. And a fear of Kurdish nationalism still prevails in Turkish foreign policy, both in the region – in Syria, Iraq, and Iran – and outside it – see Sweden’s present struggle to join NATO and various altercations with the US.

Erdogan’s dream.

Unlike every other modern Turkish ruler before him, current leader Recep Tayyip Erdogan has added a neo-Ottoman patina to the Kemalist dream - invoking the legacy of both the pre-1922 Ottoman Empire and Islam.

In particular, Erdogan’s model is Sultan Selim I, under whose rule (1512-1520) the empire more than doubled in size to dominate the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean, gained control of the world’s most important trade routes, and earned the title of caliph after conquering Mecca and Medina.

Like other neo-imperial countries, Erdogan’s Turkey is marked by elevated regional ambitions, growing religiosity, and sustained public appeals to national greatness. It is also moving away from its “western”, “secular” and “modern” face that Turkish leaders have generally tried to present to the world.

Such appeals resonate with the people of Turkey’s Anatolian heartland, who are pious, conservative and fiercely proud. Theirs is a humble, soldierly pride, harking back to the national mythology of a warrior caste of nomadic Turkics who conquered Constantinople, and culminating in Atatürk’s ferocious repulsion of much larger imperial powers in the ‘Independence Wars’ of the early 20th century.

Put simply, Erdogan wants Turkey (and himself) to be seen as big and important and tough: a country (and a man) of consequence, befitting of its warrior genes and glorious past.

Turkish delight.

And, it’s true to say, Turkey is indeed a country of consequence.

Turkey has the 11th most powerful military in the world. It is an essential member of NATO. And it has an enormous defence industry.

Though its spending as a share of GDP is low by the standards of smaller states, Turkey has developed its own sophisticated weapons, having been cut off from buying American technology for decades. Today, it exports to over twenty countries. These ties colour its bilateral relations.

Turkey also matters economically - and not just as a trading hub. Despite its well-known problems with inflation and monetary policy, Turkey has the 17th-largest economy in the world (and the 7th in Europe). It has a major state-subsidised construction industry, an “aid” agency that mostly promotes Turkish-led infrastructure developments in the region, and an outsized influence in certain African countries (particularly Somalia and Ethiopia).

In an increasingly multipolar world, Turkey is able to flex its muscles.

Turkey’s growing influence derives from being one of the few countries able to maintain good relations with both Russia and the West. Turkey is a longstanding ally of the US, which tends to give it a free ride on human rights and foreign policy, despite frequent antagonisms. In recent years, Ankara has made serious efforts to improve relations with neighbours (including Israel after several years of severed relations following the IDF killing Turkish activists aboard the original “Gaza Freedom Flotilla” in 2010). And Turkey remains less reliant on Chinese investment and less subject to its influence than many other so-called “geopolitical swing states”.

Free of ideological pretensions (besides a patina of Islam), relentlessly pragmatic, and needed by both the West and its foes, Turkey can be a diplomatic bridge. UN Secretary General Antonio Guterres turned to Erdogan to help broker the Black Sea Grain Initiative, not only because Turkey had a stake in the region, but because it was possibly the only country in the world able to transact with both Russia and Ukraine.

Similarly, while Russia is focused on Ukraine and distracted from Central Asia, Turkey has been acting to offer the Turkic states a “third way” - a relatively easy sell given a common cultural, linguistic and ethnic heritage.

But even pragmatism has its limits. The Turkic connection with China’s Uighurs has created a lack of trust with Beijing and is a principal reason for the relatively underdone bilateral relationship. Despite its geographic advantages, Turkey remains the weakest link in China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

Balancing act.

Turkey’s pursuit of EU membership has been a feature of its foreign policy since the 1980s. For now, however, it is definitely on hold. Neither side appears ready to grant what the other side wants (for Turkey, better visa outcomes for its citizens and lower tariffs; for Europe, adherence to its democratic governance standards, especially as Erdogan centralises power and erodes civil liberties).

But neither seem to worry too much. Accession has been put on the backburner and the EU and Turkey still maintain transactional relations, even if those are sometimes fraught. And the status quo suits both parties quite well. Most EU states are happy not to have a giant Muslim country join their club. And Erdogan doesn’t want to give up any control to Brussels.

Turkey does not need to be a full member of the EU.

While fewer trade restrictions with Europe would be desirable, more important for Ankara is being able to balance its foreign policy and extract concessions - from East or West - in its interests. Ditto for its NATO membership, which Turkey uses as leverage both with Russia and European countries - as Sweden found out recently when Turkey protested its inclusion on the grounds it was not doing enough to deal with what Turkey considers Kurdish terrorists.

Ankara, on the other hand, has had less success balancing its economy of late.

Erdogan’s early tenure was marked by quickly improving economic conditions following radical structural reforms, imposed by the IMF and World Bank. But in more recent years, Turkey has adopted unorthodox economic policies, under the president’s supervision, leaving the economy in bad shape. Living standards have declined, the middle class has been squeezed, and inflation has frequently exceeded 100 per cent.

Observers often struggle to understand why Ankara kept interest rates low while inflation was high. Explanations for ‘Erdonomics’ range from the theoretical – in which Erdogan genuinely believes, as he says he does, that high interest rates are a cause of inflation rather than its remedy – to the theological – born of a Muslim distaste for interest rates.

They also include the conspiratorial: Erdogan was intentionally devaluing the lira and buying up foreign currency for his family, or for venal interests, or that he was swapping favours for investment opportunities. Elsewhere, many pragmatists argue the Turkish president, as a businessman, thinks low borrowing costs spur economic growth, jobs, and attract foreign investment, while keeping exports competitive; which is all sound when the economic cycle is favourable, but disastrous when it is not.

Whatever the reason, following Erdogan’s re-election in May and several new economic appointments, the government appears to be returning - albeit slowly - to more traditional economic management. Thursday’s move to raise rates by 5 percentage points to a hawkish 40%, are a case in point. With the winter months approaching, Turkey needs to give its citizens more spending power for their lira and more food on the table.

Last Week’s Poll Results.

Last week, you might recall, we wrote an essay on the “wisdom of the crowd” and conducted a poll asking you to forecast geopolitical developments related to China and Taiwan. Here is your collective wisdom - and our comments:

Question 1: Who will win the Taiwanese elections in January?

Answer: The ruling pro-independence DPP (74% of respondents).

Well, you're on the money there. On Friday, the two main opposition parties tore up their mooted alliance, which will split the non-government vote unless something dramatic happens in the meantime. So does this mean more difficult cross-strait relations ahead? Probably, but as seasoned election-watchers know, what a candidate says on the hustings and does in government are two very different things. Both Taipei and Beijing have incentives not to upset the delicate status quo. The real wildcard, as always, will be what happens in Washington.

Question 2: What is the probability China will take military action to force "reunification" of Taiwan by end of 2027?

Answer: Less than 20% (50% of respondents).

We hope you're right and think you are. Again, both sides are incentivised to pursue peace, whether that means maintaining the status quo or something else. Yet 20% is still, in probability terms, a dangerous level for a calamity that could cause WWIII. And a good minority of you believe there's a more than even chance...

Question 3: What is the probability that the US and China will announce plans for an arms control agreement on artificial intelligence by the end of 2025?

Answer: Less than 20% (37% of respondents).

This one had a pretty broad range of opinions, which says to us that we just don't have a clear indication yet. And with the term 'artificial intelligence' so vague it's no wonder. Perhaps a better question is: "will the US and China have an agreed definition of artificial intelligence by the end of 2025?" Perhaps something to ask ChatGPT...

Question 4: China's third-quarter economic growth was 4.9%. What will China's fourth-quarter economic growth be?

Answer: 3-5% (70% of respondents).

Extrapolating a trend is easy so we're not surprised. And you're in good company with economists surveyed by Bloomberg.

Question 5: What is the probability that China and ASEAN will sign an agreement on a South China Sea 'code of conduct' by the end of 2025?

Answer: Less than 20% (62% of respondents).

Again, extrapolating a trend is easy and the trend has consistently been to kick the code of conduct can down the road. Indeed, as we've said before, the code of conduct is a perfect mechanism to justify ongoing diplomacy while acting in bad faith. Anyone familiar with the Minsk agreements of 2014-22 will be familiar with the playbook.

Question 6: What is the probability that the US will impose further controls on semiconductor chips by the end of March 2024?

Answer: 60-80% (30% of respondents).

Like the question on artificial intelligence, this also had a broad range of answers, though skewed on balance towards the probability of further controls. And in a US election year, with Republicans belatedly seeking to differentiate themselves on China, we may indeed get more pressure for trade-restrictive policy.

Thanksgiving.

Thank you again. We hope you found these results insightful and look forward to presenting your views on Turkey-related questions this time next week.

We hope you are enjoying Geopolitical Dispatch. If so, we would appreciate it if you could share with your friends and colleagues. Happy Thanksgiving.

Best,

Michael, Cameron, Damien, Yuen Yi, Andrea, and Kim.