Week signals: Back on the mainland

Plus: watch points for Russia, China, the US, Central Asia, and Hungary.

Hello,

In this week’s edition of Week Signals:

IN REVIEW. Eternal wars, eternal questions; the opiate of foreign policy; compellence and coercion.

UP AHEAD. Russia and China; elections in America; tariffs at court; the ‘stans (and Viktor Orban) go to Washington.

And don’t forget to connect with me on LinkedIn.

Week Signals is the Saturday note for clients of Geopolitical Strategy, also available to GD Professional subscribers on Geopolitical Dispatch.

The Week in Review: Addicted to intervention

Co-authored with Oscar Martin.

The week began with Donald Trump beginning a gold-plated tour of Asia. It ended on his return with plenty of baubles but also plenty of debate on how much had really been achieved. The reconstruction of the White House and America’s body politic continued – with new images emerging of a garish 80s-style bathroom, which the president somehow described as “very appropriate for the time of Abraham Lincoln” – but so did the government shutdown, with today being the critical date when for many Americans its first effects will be known (more in The Week Ahead, below).

Also continuing was the Trump administration’s controversial war on drugs in the Caribbean and eastern Pacific, which the UN’s human-rights chief Friday called a violation of international law. Such a reaction was expected. And we expect it will be ignored. But what is perhaps more uncertain is whether these strikes will go from sea to land, and specifically, to the mainland of Venezuela.

The Miami Herald and the Wall Street Journal claim such attacks could be imminent. Trump himself claims they’re not. The Venezuelan opposition is reportedly divided, but Nobel laureate and self-described Trump ally Maria Corina Machado told Bloomberg that escalation was “the only way.”

Should that be so, now is the time to ask why, so soon after both sides of politics vowed not to repeat the follies of Iraq and Afghanistan, the US is again eyeing another war of choice. Why is the US, with natural borders and no true proximate threats, risking another quagmire in a poor but oil-rich country? Will the potential benefits outweigh the likely costs? Is the US as addicted to intervention as to narcotics? At least two of these questions are inherently unknowable, but our Paris-based analyst, Oscar Martin, takes a look.

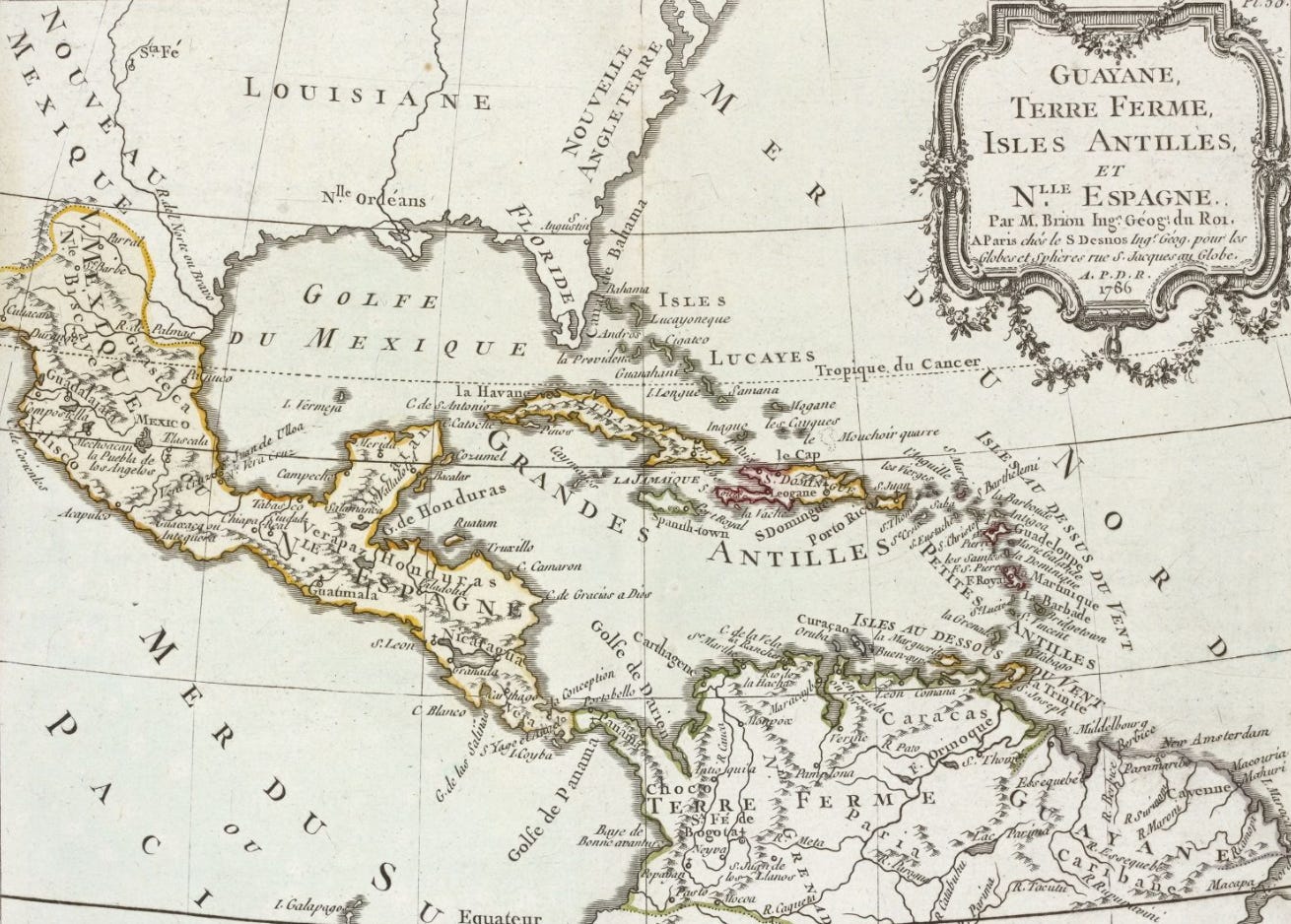

This week, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro accused Washington of “fabricating a new eternal war” as the United States launched its largest naval deployment in the Caribbean since the Cuban missile crisis. The arrival of the USS Gerald R. Ford, the authorisation of CIA covert missions and a string of B-52 overflights mark a sharp turn for a president who once promised to stay out of foreign entanglements.

These actions recall the second half of the twentieth century, when Washington intervened across Latin America to contain leftist movements. As the Cold War waned, the focus shifted to narcotics.

The war on drugs continued into the next millennium. Washington’s largest foreign aid programme outside the Middle East, Plan Colombia, combined military assistance, intelligence support, and aerial fumigation to suppress coca cultivation and weaken the FARC insurgency in Colombia.

In the 21st century, the war on terror in the Middle East dominated US foreign policy. Trump is now bridging that logic with the war on drugs, as part of a broader push to reassert US power in the Americas. In his first days in office, he designated the cartels as foreign terrorist organisations, giving the war on drugs a legal framework closer to counterterrorism than policing.

The domestic crisis is real. Fentanyl remains the leading cause of death for Americans aged 18 to 45, killing more than 70,000 people a year. The drug has been (not inaccurately) described by Trump as “a weapon of mass destruction pouring across our borders.” This reality lends legitimacy to the Trump administration’s aggressive policies.

It formed the justification for imposing tariffs on Canada earlier this year, despite less than 5% of fentanyl seizures occurring on the northern border, according to US Customs and Border Protection. Ottawa responded by appointing a national ‘fentanyl czar’ to coordinate enforcement and public health policy, a gesture of compliance more than conviction.

In Mexico, the same narrative was a pretext for tariffs. Citing fentanyl and migrant flows, Trump imposed 25% tariffs on Mexican steel and automotive parts. The tariffs were paused for negotiations, with a deadline of 1 November, which has since been extended. He also ordered National Guard deployments to assist joint patrols inside US territory, blurring the line between trade enforcement and military deterrence.

The pattern of the administration’s policies is selective. This week, the administration reduced fentanyl-related tariffs on China as part of trade negotiations. This illustrates the transactional nature of Trump’s actions, which is now being applied with increasing force to US neighbours, particularly Venezuela.

Trump has authorised CIA covert operations in Venezuelan waters under a “narco-terrorism” directive. The narco-terrorism directive provides the bridge for US intervention in the Americas. It combines America’s two most resonant crusades—against drugs and against terror—into a single licence. It collapses the legal distinction between law enforcement and military operations.

The case of Venezuela shows how that licence is now being used. Trump called Venezuela a “terrorist narco-state”. Maduro accused Washington of planning a “false-flag” operation in collaboration with the CIA and Trinidad and Tobago, after a US destroyer docked at Port of Spain for joint exercises.

Washington says the campaign is aimed at drug traffickers using Venezuelan waters. Yet the scale resembles a military blockade. The US has been pressing Caribbean governments to participate in a campaign that has already left 43 killed, across several boats, including several civilians with no apparent ties to Caracas. The White House has given no clear account of rules of engagement or jurisdiction, but Secretary of War Pete Hegseth recently announced Admiral Alvin Holsey will leave Southern Command, amongst apparent sparring regarding the legality and nature of the strikes in the region.

Trump’s framing of Venezuela as a terror state marks the first overt use of the terror label to describe Latin actors since the 1980s. Alongside Machado’s recent Nobel Prize, pressure is increasing on Maduro. For Maduro, the situation amounts to a slow-motion justification for war. For Washington, it is the reassertion of unilateral power in the region.

In Argentina, the US is applying the same strategy through finance rather than force. A strategy of “compellence” rather than coercion. Trump has courted Javier Milei as a key ideological ally in the region. Since Milei’s mid-term gains, the US has offered a $20 billion currency swap, alongside a further $20 billion facility from private sources. The sum roughly equals the budget cut from USAID earlier this year under America First cost-savings.

For Milei, the package offers immediate liquidity relief in an economy facing 50% inflation, dwindling reserves, and a dollar shortage that has throttled imports. For Washington, it buys a partner who speaks the language of market liberalism and anti-statism. US Treasury officials describe the support as “technical cooperation,” but it functions as conditional access to dollars, politically inexpensive leverage compared with troops or sanctions.

To neighbours already wary of US overreach, the cases of Canada, Venezuela, Mexico and Argentina all show that Trump’s transactional foreign policy is being applied with full force in the region. Trump is building a strategic toolkit, rather than a concerted set of policies. Drugs provide the moral narrative; “terrorism” supplies the legal mechanism; trade, intelligence and finance are the instruments. The combination allows the White House to operate simultaneously through economic and military channels with minimal congressional oversight.

The risk is that an increased US presence will produce old results. Historically, counter-narcotics interventions have had marginal or limited impacts on availability in the US, and militarised interventions would be more effective alongside peace-building activities. These interventions achieve temporary control at the expense of legitimacy. The current campaign, despite its updated vocabulary, faces the same structural problem: it is built on political performance, not outcomes.

The revival of US interventionism under a “narco-terror” banner will complicate regional risk and investment planning. Firms with supply chains or assets in the Americas should expect greater policy volatility, uneven enforcement, and rising exposure to sanctions and tariffs framed as security measures.

Financial flows may increasingly be politicised, with access to dollars or credit conditioned on alignment with Washington’s agenda. Energy, logistics, and agribusiness operators face the sharpest exposure as trade corridors militarise. For business, the message is that the US is forcefully cementing unilateral power in its backyard, and with that comes increased volatility and instability, no matter what the real intended outcome might be.

The Week Ahead

CHINA. RUSSIA. Watch for defiance

On Monday, Prime Minister Mikhail Mishustin will meet Premier Li Qiang in Beijing. After Trump’s meeting with Xi Jinping last week, it will likely be an overlooked coda, but its outcomes could be more enduring. Mishustin is expected to secure Chinese undertakings to continue buying Russian crude, with the limited evidence so far of US sanctions on Lukoil and Rosneft suggesting they will. Mishustin will also be keen to accentuate, as the Kremlin tries every day, how Western policy is not just being ignored, but is increasingly futile. Trump has tacitly acknowledged this, saying he didn’t ask Xi to stop buying Russian oil while in Busan, but if Beijing and Moscow press too hard, such as announcing new currency cooperation, which particularly worries Washington, the gloves could come off.

UNITED STATES. Watch for a shutdown referendum

On Tuesday, New Yorkers vote for a mayor, New Jerseyans and Virginians vote for a governor, and Californians vote for redistricting. These and elections in 29 other states all have very local dimensions, but in aggregate will be seen as a referendum on the federal government shutdown, particularly with the impact of food stamp cancellations, Obamacare hikes, and transport safety payrolls, likely to begin to bite. Surveys show a plurality of Americans continue to hold the Republicans responsible for the impasse, but blame is also growing for the Democrats. The elections could be the clearest signal yet of just who voters will find liable, and therefore what the Senate will do next.

UNITED STATES. Watch for justice on trial

On Wednesday, the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments in two challenges to Trump’s ability to impose tariffs without clearer legislative authority. The case is in many ways highly technical but verdicts from lower courts were relatively clear cut and thus the decision will be seen as a loyalty test as much as a question of jurisprudence. Most judges continue to claim that any partisan affiliation ends at the door but voters don’t see it that way, with trust in US legal institutions declining alongside those of the executive (Congress has always been distrusted). No matter the verdict, the bench will go to pains to explain itself in legal, not political, terms but watch for the dissenting opinions.

CENTRAL ASIA. Watch for the missing players

On Thursday, Trump will host a summit of the ‘C5’ Central Asian leaders. The presidents of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan are expected to attend, but the ‘stans that Trump is thinking about most - Afghanistan and Pakistan - won’t be there. Beyond that, the influence of China, Russia and India, in that order, will be top of mind for all participants, in a crossroads region that has occasionally attempted to exercise agency but has traditionally found its internal differences, sparse population, and landlocked geography to be insurmountable. There’s little Washington can do in Central Asia without the involvement of one or more of the region’s sea-facing neighbours. This held for the war against the Taliban, and so too for any deeper economic cooperation, including on rare earths.

HUNGARY. Watch for overreach

On Friday, Viktor Orban will visit Trump at the White House. The president’s “best friend” in Europe will be seeking support for oil sanction waivers, as well as another go at holding a summit with Vladimir Putin, but he risks overplaying his hand. Orban has successfully balanced Brussels off Moscow for years but Washington is a different beast and in Trump a fox knows its own kind. Having dispensed with and humiliated other toadies before, Orban has as a fickle friend in Trump as he does in Putin. Orban is also doubly vulnerable in the lead-up to next year’s legislative elections where all stops, including ownership of a remaining semi-free newspaper, are being pulled out to prevent opposition leader Peter Magyar from riding a wave of popular discontent with Orban’s increasingly illiberal regime.

Thank you for subscribing to Geopolitical Dispatch. Feel free to contact me with any questions or comments.

Best,

Michael Feller, Chief Strategist

michael@geopolitical-strategy.com

This briefing is for general information only. It is not legal, financial or investment advice. Information and opinions are current at the date of publication and are subject to change without notice. There is no representation or warranty as to its accuracy, completeness or reliability, and no liability for any loss arising from use or reliance on this information is accepted.